Wild Kinship: Saving the Amazon to Save Ourselves with Paul Rosolie

Guarding the rainforest’s last sanctuaries—and the choices that could let life flourish.

Paul Rosolie is a conservationist, author, and award-winning wildlife filmmaker focused on protecting one of the most biodiverse regions on Earth: the Amazon. For nearly two decades, he has worked in Peru documenting rainforest destruction and the illegal wildlife trade—often traveling alongside poachers to expose the networks threatening endangered species. His memoir Mother of God was praised by Jane Goodall and the Wall Street Journal for its gripping call to action, and his short film An Unseen World earned recognition from the United Nations.

Rosolie is the founder of Junglekeepers Peru, an organization safeguarding over 110,000 acres of primary rainforest while employing and empowering local rangers. Through his work, he combines storytelling, filmmaking, and direct action to defend the Amazon at a critical moment. With Junglekeepers as his central focus, Rosolie is helping shape a new model of conservation—one grounded in long-term commitment, local leadership, and an unshakable devotion to the living forest.

The following interview has been transcribed from audio, with some revised sections.

INL: You’re a New Yorker who has dedicated himself to protecting the Amazon. What led you to venture into the rainforest—and what deepened your commitment to its preservation?

Paul:

INL: How has living in the Amazon changed your understanding of life, survival, and what it means to be human?

Paul: Hmm, great question. 50% of the people on Earth right now live in cities. With that comes a lot of things. There's a huge disassociation from our tribal roots and the way that we're supposed to live. There's a lot of isolation in a societal sense, but there's also isolation from nature. Your food comes from the grocery store. Your meat comes in a package. Famously, they asked kids, "Where are the animals?" They said, "At the zoo." "Where does chicken come from?" "The grocery store." People are fundamentally disconnected from these things. Whereas, for all of history, we depended on salmon in the rivers. That’s an entire community—with fishing villages by the sea or hunting deer. Those things were staples that we depended on. And so we valued them.

That’s why conservation became a thing. Darwin, even in his time, saw the destruction and understood—we can't keep this up. Teddy Roosevelt saw it too. John Muir invited him out west and said, we have to protect the sequoia trees or they’ll be gone—the biggest trees on Earth. He said, “You have to come out here and see it.” And he brought the president out to see it. That’s how they started the National Park System1.

So there’s a history of that. But living in the rainforest—you’re incredibly connected to everything around you. The way I got introduced to it was through the Native people. A lot of PhDs come down here. They wear their gumboots, and they go with a group of foreigners to a research station, where they have a director, and they calculate the ecosystem. I was barefoot, with a bunch of wild guys, out in the middle of the jungle. These are people that grew up there. They had generational knowledge—a few thousand years passed down: how to treat wounds using forest medicine, how to treat a snakebite, how to cure infection.

As a New Yorker, there was part of me at first that said, “Oh, this is probably the kind of medicine that you have to believe in for it to work.” No. These are heavy medicinal compounds flowing through these plants. There are medicines in the Amazon. The Amazon is where the first cure for malaria came from. It’s where rubber came from. Bushmaster2 venom was part of Captopril, a blood pressure medication in the '90s. There are all kinds of medicines coming out of nature. That’s where we get our initial medicines from.

So for me—from the age of 18 to, sounds crazy, but to 37—I’ve probably spent more time in the jungle than anywhere else. At this point, I sleep outdoors more each year than I do indoors. I’ve really lived incredibly connected to the wild. I drink from the streams.

JJ showed me this incredibly powerful thing one day. We were walking up a stream in a very, very remote part of the jungle—beautiful, pristine stream, jaguar tracks everywhere, harpy eagles and macaws in the trees, spider monkeys, stingrays in the water.

We were drinking from the stream. We’d do this every day. We’d go fish, and we’d drink from the stream and everything. One day, I was drinking from the stream, and he stopped. He said, “Look.” And he showed me my own arm. The sun was hitting my skin. And in the cool shade of the forest, there was this beam of light, and it was pulling the sweat off my skin. You could see it. You could see it emanating off your body.

When you see that, you feel like something magical is happening. Then what you realize very quickly is that that magical thing is happening all the time. It is pretty magical that we’re drinking from the stream, and then the sun is lifting that same moisture right out of our bodies, off our skin, into the air. You can watch it come off the forest. It looks like the forest is breathing—you can see the smoke coming off the forest and joining the clouds.

Then every afternoon, there’s a thunderstorm. And it all rains back down. Then you drink it again. You’re part of this system. That sort of tangible, sacramental reality is in front of you. It makes you consider the blending of science and spirituality. I don’t know where they ever became enemies—because down in the jungle, they’re braided. It’s the same thing.

It makes you consider the blending of science and spirituality. I don’t know where they ever became enemies—because down in the jungle, they’re braided. It’s the same thing.

It makes you really question the whole thing. You go, "Wait, hold up. So we live on the crust of this planet. We can’t go up the mountains because there’s no air—we’ll die. We can’t go to the bottom of the ocean—we’ll die.” We’re just on this tiny, tiny microclimate on this one planet. No matter how much people talk about aliens or water on other planets, the truth is, we don’t have a single cell, a single fingernail, a wingnut—anything—to prove that there’s any other extraterrestrial life.

So, as much as we say, “The Fermi Paradox, they have to be out there,”—sure, sure, sure—but as far as we know, this is the only place where life exists. Here, in the wild, it exists in such incredible abundance. It makes you think—when you look at Google Earth, or the coast of the US, or Europe, India, Indonesia—what we’re doing to nature. You realize how inextricably integrated we are with natural systems—that then destroying them becomes a kind of self-inflicted wound. What are we doing? Why are we allowing this? Why aren’t we horrified by it?

Then when you go back to the city and see everyone’s screaming about a sports match, or cell phone plans, or what a politician did or didn’t say. You’re like, “Oh. It’s the Roman circus.” You people have no idea what’s going on. You feel like this messenger, like you’ve been woken up—and everybody else isn’t getting it.

Living in the wild connects you to animals, too.

First of all, look at domesticated animals. Apples, bananas, oranges—those were made by people. We bred them to be what they are. Same with corn—there were two grains on teosinte, and we bred it into corn. Same with potatoes, tomatoes—all the things we use. Ancient peoples selectively bred those to be more abundant, to have more fruit, and less seeds, and to be more plentiful on the plant. They did that for us. Those are domesticated things. A golden retriever—I love them, I grew up with them—but it’s not a real animal. It’s a domesticated animal. We made those. And forget pugs—that’s just animal abuse. They can’t even breathe.

But in the wild, when you deal with wild animals—well, wild animals for most people, again, where do they see them? The zoo. Or a fleeting glimpse of a fox across the road. You don’t get any insight into their minds, how they solve problems, what they care about, what tragedies they have, or what culture they have. I mean, animals pass down culture. Mother monkeys teach their children which plants they can and can’t eat. A mother tiger teaches her cubs how to hunt. Which is why—this is a crazy fact—no tiger born in captivity has ever been reintroduced into the wild. Because humans can’t teach a tiger all the things it needs to know to live in the wild. It needs to be taught how to wait, how to hide, how to stalk, how to kill, how to asphyxiate prey. Only a mother tiger can teach that. So anytime you have a tiger bred in captivity—it’s useless in the wild. It can only be a mascot, an ambassador in a zoo. It can live in a zoo, if you really want.

But thankfully, some animals—like rhinos—are like big lawnmowers. You can put a rhino back in the wild after it was born in captivity. It'll happily eat grass the rest of its life, and find another rhino to mate with. But for a lot of these animals, it's incredibly complex.

I've spent a lot of time with animals. I've spent a lot of time raising animals. I've had injured toucans that I rehabilitated. I've had giant ant eaters that I rehabilitated. I've lived with semi-wild elephants, because then I started doing work in India as well. When you live with wild animals, you see this whole other side of them that you just would never, ever imagine—that they're so much more complex and smart.

I mean, I've seen an elephant stop and suddenly look at this one village girl. It was a gigantic elephant—12 feet tall—backing this girl up against this mud hut and putting her trunk out against the girl's stomach, touching her. Elephants communicate in a frequency that we can't hear. All the other female elephants came, and they were all touching this girl. She was terrified. She dropped her books and was just standing there. And one of the locals explained to me, using sign language, "She's pregnant. The elephants know."

This is why you can can run through a city and a police dog will follow you all the way through the city. To them, scent markers are just as visual as wanted signs along the way, like a trail blaze. They can follow that scent mark. Animals know if you're stressed. They know if you've been sleeping well. They know if you're sick. They know if you have your period. They know if you've been in an argument recently because your levels are elevated. That’s why they have dogs that can smell when a person with type 1 diabetes is having an insulin issue.

Animals have so many faculties that we don't have. I mean, they see on visual spectrums that we can't imagine. They smell things that are far outside our range. They communicate in frequencies that we can't hear. You start to question: Why are my two-legged people destroying everything for all the four-legged, the scaled, and the finned? We're messing it up for everybody.

All these animals are out here. It’s the birds that are carrying the seeds from plant to plant, and the hummingbirds that are pollinating the flowers and keeping everything going, and the bats are carrying seeds. You start to realize, oh my God—they make the jungle. The animals don't live in the jungle. They make the jungle. It's all connected. When you're there, you're part of it. You have to live within the boundaries of that. We have forgotten all of that. We have long forgotten all of that.

When I now look at society, and I see how lost people are, and how everyone's looking for the next… you know… everyone's on ayahuasca tourism and trying to do cold plunges and listening to a podcast about breathing and all this stuff—everyone’s friggin’ lost because they're not connected to the things. We're a species that's perpetually a fish out of water. Everyone's looking for the answer. Everyone's looking for why do I feel so uncomfortable? Well, because you're not living the way you're supposed to. None of us are. Because we're living in air-conditioned, sterile environments where the ground has been leveled and paved for us, and where the food is in the store. If you get in trouble, somebody's going to help. So, you don't need to rely on the people around you. And you're pursuing money, and so you move away from your tribe and your parents.

Everyone's looking for the answer. Everyone's looking for why do I feel so uncomfortable? Well, because you're not living the way you're supposed to. None of us are.

In villages, girls don’t have postpartum depression because their aunts and their mother and their sisters and their friends are all there. And they all also have babies. It's a community. It’s totally different. All these modern problems are largely to do with the fact that we've completely amputated ourselves from Mother Nature.

INL: Junglekeepers protect over 110,000 acres. But the real work is relational: staying in rhythm with the forest, the people, and the pressures that threaten them both. What does it actually mean—on a lived, relational level—to be stewards of the forest? What kinds of decisions, interactions, and threats do you face every day?

Paul: In order to protect the land, you have to understand the connectivity of everything—that the animals, the river, and the forest are all inextricably braided together. The people who live in the Amazon depend on the fish in the river. They depend on the trees. They depend on the water being clean.

If there were an oil spill, they wouldn't be able to drink the water, and they have nowhere to buy it. They don't have bottled water. If something were to mess up that river, the fish stocks would be gone. The people would starve. Everything is connected. And it’s actually still in balance.

In order to protect the land—which we do have to protect—there's a nuts-and-bolts reality: there are invaders and narco-traffickers coming in who want to settle the Amazon. They see it as free space. They can come and take it, shoot the people living on it, burn down the jungle, and grow papayas, cocaine—whatever they want to grow. So, there are bad guys killing the forest. And there are a bunch of Indigenous people in the middle who are trying to live an indigenous lifestyle, and seeing their environment change. They'll often say, "When I was a kid, there was so much fish in the river, you could eat whatever you wanted."

The reason JJ became a conservationist was because where he grew up, they got all their food from the forest. They had a few chickens, but most of their diet came from monkeys, fish, and forest fruits. But by the time he was a teenager, his community, as chainsaws, shotguns, and boat motors came in, all of a sudden, humans could move faster and they could harvest more. That ancient sacred balance got destroyed as the technology came in. He saw all of these things get destroyed. He went deep into the jungle, to our river, because it was still wild. But then the threat came to our river, and we saw it for ourselves.

The nightmares I’d heard about as a child—deforestation, logging, gold mining—became real. With them came prostitution, human trafficking, and drugs. As people kill the forest, they bring with them a black market for timber that goes to China, and wildlife sold to resorts. Where there are teams of men working in the wild, someone decides they want prostitutes. So they steal girls from the communities and traffic them. There’s a human trafficking element to all of this.

In order to protect and heal, we have to rehabilitate people in many senses.

Initially, when I came down here at 18, if you asked me, I probably would have said I think it would be cool to go fight the loggers—something basic and testosterone-fueled. Then you learn the loggers are your friends. They're local people with families who have no better way of making a living. So, they cut down some trees and work for a logging boss for $10 a day. They do hard, dangerous work in a jungle they love and want to protect. But this is the narrative: this is how you make some money to put some food on the table now, because you’re dependent on the economy and capitalism.

Of course, if there's gold mining, then there's mercury contamination in the area. Once people start coming into these Indigenous communities, immediately there's soda, and Coca-Cola, and Inca-Cola, and all of these sugary drinks that all of a sudden the people start becoming obese. And you start seeing Indigenous people that are just crazy obese, because they drink so much sugar, because they love it, and no one told them that it's bad for them, and they start eating rice, because rice gets brought in on sacks. And so instead of having limited resources and lots of protein, they start having high carbs, highly processed—and then tons of sugar—and they become obese. Then, of course, that also makes them want to not walk as much.

So everything changes, and the cycle is thrown off.

When we started Junglekeepers, the first thing we saw was a place where ancient ironwood trees were being cut down. In the Amazon, land is now either a national park, an Indigenous reserve, privately owned, or state land. Well, we live in a world of countries—there’s some sort of legal designation for every bit of land. When we looked at this piece, and because JJ is local, we went and we spoke to the loggers. We asked, “What are you guys doing?” They said, “Oh, cutting down ironwood trees. Shihuahuacos.” Shihuahuacos are important because they grow to be a thousand years old. They are the only nesting site for red and green macaws, which are these incredibly beautiful birds that exist down here in the Amazon. And populations of macaws have plummeted all across Central and South America. There's only about 16 or 17 species of macaws, and most of them are endangered or extinct. And down here we have scarlet macaws, red and green macaws, chestnut-fronted macaws, military macaws—we have all these macaws. They're just rainbows across the sky. But that’s because they have the shihuahuacos.

So, a thousand-year-old shihuahuaco tree—this is a really beautiful interaction between the species—and everything in the jungle is connected—but you need an old tree. You need a branch to fall off. And when the branch falls off, it creates a hole in the tree, and then macaws nest in that hole. In any given year, only about 17% of the macaw population can reproduce, because they need those nesting sites that are in those trees.

In the entire infinity of the jungle—just imagine jungle from horizon to horizon—you could just put pins in the places, and every 10 acres, there may be only one or two of those nest sites available. So there's a limited amount of resources and a limited amount of macaw real estate. So these trees are super important—not just to the macaws—but to the thousands of other species: reptiles, amphibians, birds, mammals, orchids, lichen—everything that lives on them. Literally thousands of species living on each individual tree.

When the loggers come in, and they cut a tree that's been growing for 1,000 years, you're not just killing that tree and everything on it—you're creating this hole in the forest. Where it used to be this generator of species—now you've created this exponential hole in the ongoing march of the species.

Every fish, every trout, every eagle, every monkey—there’s got to be enough habitat and enough food, and they have to continue to reproduce. Otherwise, they cease to exist. So when you cut these trees, you see resounding impacts across wildlife populations.

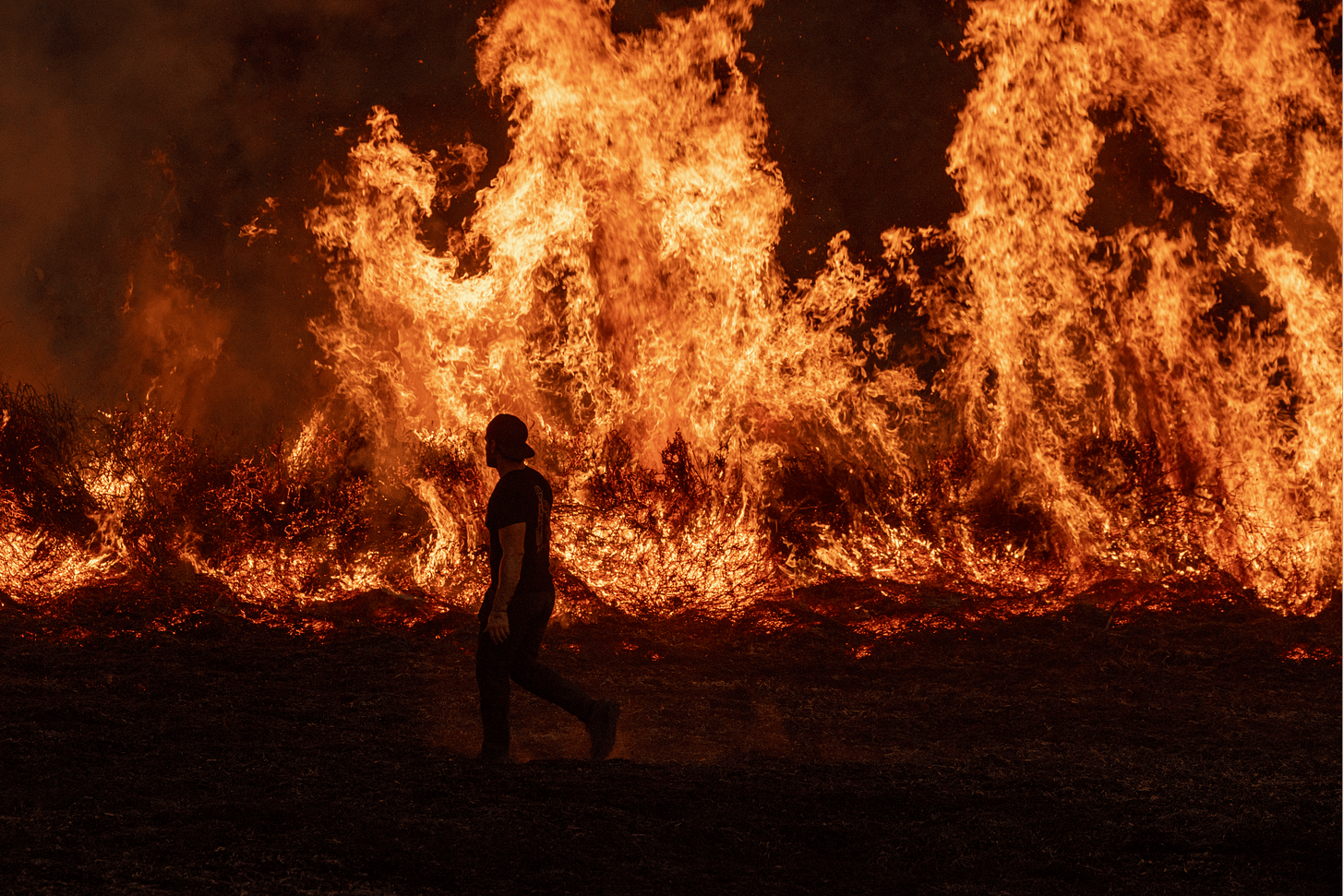

We started seeing these trees get cut. And that same stream that we were exploring—where we saw the mist coming off our skin, and we saw the moisture cycle—that this beautiful, like a piece of Eden, this absolutely untouched, gorgeous stream—they just burned it to the ground. It was destroyed. We saw that.

These things mentally maim you after a while, when you see them in real life, and you see all the places you loved burned down, and the trees laying on the ground, and the animals are all dead. And the people don't care, and they don't know any better.

So we said, “Listen, you cut how many ironwood trees on this piece of land?” And they said, “Well, so far we’ve cut 80 ironwood trees on this piece of land, and it’s only 2,000 acres.”

Then we said, “Oh, okay. Well, can we buy it from you? And can you stop?” And they said, “Well, we're almost done. There's only six or seven of them left.”

We were able to raise a little bit of money and buy it from them. And around that time we started saying, we're the Junglekeepers. This is where you start—you start manifesting. You start speaking it into reality.

I just started telling everyone, “I'm working with the Indigenous people in the Amazon, and they're fighting to protect their forest. And we're doing this thing called Junglekeepers, and we're working to protect the forest.” So, we protected our first little plot.

All of a sudden—bang—we were the reason that this plot of land was not completely destroyed. All of a sudden, we were Junglekeepers. And now we had a few million little heartbeats of monkeys, and lizards, and snakes, and birds, and all these things living in the forest.

All of a sudden—whoa—we're responsible for them. That would be black earth if it wasn't for us. Now it’s 160-foot-tall jungle, singing with birds and, throbbing with frog song.

That was really magical, to suddenly be doing something [for the forest]. To suddenly actually have a skin in the game, and to have that responsibility of knowing that there's animals and an entire ecosystem that’s safe because of us. So we ran forward with that. We started telling everyone about it, and we made ourselves into an NGO, a non-governmental organization.

We began hiring rangers. And what we discovered was: if you ask these loggers, “Would you like a better job? How much do they pay you?” “Ten dollars a day.” “Well, how'd you like to make three times that, and have medical benefits, and a steady paycheck, and be part of a community, and have other friends that are rangers—and protect the forest instead of destroy it?”

Everyone’s like, “Wait, I don’t want to be destroying this forest. I grew up in this forest. I would love that.” And we’re like, “Great.” So, they come right to us. We don’t have to fight anybody. It’s a win-win-win. We're just providing better jobs and safer jobs.

Then, of course, we ended up educating and helping them and trying to get their kids to school. It becomes this thing where you're bettering the life of the people in the region. Because if you uplift the life of the people in the region—if they’re not stressed about where they’re getting their next meal from, if they achieve a certain level of wealth to the point that they can live and think and go, Okay, this is where I want my kids to go to school, over here, because they have a better chance of learning and maybe getting a better job than we had. And I want to build my house and do this… —all of a sudden they go, We need to protect more forests.

Yeah, we do need to protect more forests. If we do this—then they have space to think. Whereas when people are stressed, and they're just trying to feed their family, and they have a sick mother, and they have a daughter, and they’re just—it’s just hand to mouth. It’s just: this meal today, right now, cutting this tree, selling this tree. That’s what I’m doing. Chainsaw. Whereas once you get them up here, once you elevate them out of that sort of desperate poverty—then they become part of the Junglekeepers team.

Now we have all these Indigenous and local people who are driving boats, and taking data points, and watching for deforestation, and working really closely with the futures of the communities.

We're now publishing scientific reports that show that in terms of mammals, there's probably more mammalian diversity here than anywhere else in the Amazon. We might have that superlative. You know, it’s just untouched headwaters.

We’re in this incredible reality now that we’re protecting 110,000 acres. And I’ve been down here—in January, it’ll be 20 years down here. It’s a beautiful thing. It’s a blessing and a burden because we’re now protecting 110,000 acres—which is half the size of Singapore. It’s so big that it takes days to patrol, to go from one end to the other. It’s too big to ever explore. There’s more of it than any human could ever see. It’s infinite in that sense. But we need to 3x that if we’re going to protect the whole river.

We started off not thinking we could do it. Then we tried and succeeded. We kept notching these little wins. Now we’re at a really strange point where we’re a major organization protecting a major amount of forest. That’s a huge responsibility. Now, 20 years later, there are more roads. The narco traffickers really want free land. It’s gotten harder for them to operate near the cities because law enforcement has improved, so the pressure is on.

They want to make these roads quick. They want to get in there. Now, there’s a new international shipping port in Lima, so the demand for logs has increased. The loggers, the gold miners, and the narco traffickers are even more motivated than ever. They see us protecting the forest and they’re like, we’ve got to destroy it before these idiots protect more of it. Now, not only do we have to fight the entropy of globalization—now we literally have to defend the land every single day.

We’ve made friends with loggers, with gold miners, with local people. But now people are pouring in from outside. Narcos are sending people here. The cocaine mafia has figured out that if they operate deep in the jungle, the cops can’t come and get them.

Things are getting very, very intense. But I use the analogy—you play as a kid, you hone as a college student, you get into the major leagues, and then you end up at the World Cup. We’re on the field. There’s no guarantee we’re going to win. Absolutely none. But we’re doing everything we can. At this point, we’ve got a shot, which is amazing.

If we fail—it’s tragic. The whole river will burn. If we fail, then we fail. If they cut a road across it, then everything was for nothing. It’ll disband. It’ll all get burned. But if we succeed, we create the first-ever national park that’s sort-of crowdfunded and wouldn’t be here without the collaboration of Indigenous experts, international scientists, and people from around the world who have donated. Social media has spread it. It’s been this incredibly modern, outside-the-box, strategic guerrilla conservation. We’ve surpassed some of the organizations I grew up admiring—in reach, funding, and ability to take action.

So it’s very serious now. We’re working with Peruvian law enforcement. They’re happy to help us. They said, if you protect all this, we’ll make it a national park. They’ll even convert it over for us.

But the price tag to get all that land before the narcos and loggers destroy it is $30 million. So, I have to raise $30 million in the next year and a half—or else we fail.

INL: Having stood in both the untouched wild and places devastated by extractive industry, how do you convey to someone who’s never been why this forest is at risk—and why it should matter to them?

Paul: I would say that in the basement of our minds, in the place we all have in dreams, it's important to us to know that on Earth, there are places that are still untouched—places that work the way they're supposed to, where the water is clean, where there are mountaintops and jungles and parts of the ocean that are crystal turquoise.

That's important to everyone—to know that even if it's not where you live, even if you're living out behind the airport, it's still true that there are places on Earth that are nice. That's important to all of us spiritually.

I think the reason I've dedicated my life to this place, and the reason that everyone else has been dedicating their lives to it—risking their lives for it on a day-to-day basis—is because we view this as the single most important thing we could be doing. The single most important way we could be spending our lives.

That's because the vitality and abundance we see here is off the charts: the undiscovered medicines, the uncontacted tribes, the endangered species, the ancient trees, the water cycle. All of these things create this alternate reality that almost seems like another world. Viewed from inside a modern city, you almost forget that things so wild could still exist. Twenty-five-foot anacondas. People still in the jungle with bows and arrows. Medicines that can murder an infection better than antibiotics. No way. Yep. It's all out there.

To those who live far away, I would say we live in a time when, if you're above the poverty line, it's your responsibility to be helping with something. It's also not your responsibility to take on the entire world's problems.

I would say we live in a time when, if you're above the poverty line, it's your responsibility to be helping with something. It's also not your responsibility to take on the entire world's problems.

At this point, I have kids messaging me—thousands of messages pouring in from kids all over the world who've read my book or seen an interview—and they say, “How do I get your job? I want to do something.” A lot of young men. Interesting. A lot of young men want to go to war. They want to be part of something important. They're dying for it, and they don't see it in their lives. They don’t see a way toward it. The first thing they say is, “I want your job.” I'm like, “Kid, no, you don’t know what you’re talking about. You don’t want my job.” It ain’t no way to spend your life.

They don’t know how many times I’ve been bitten, stung, stabbed, bled out, gotten tropical diseases, been run over by boats, chased by narco traffickers. That’s not fun stuff. You have to do a lot of healing. You end up with a lot of scars.

The encouraging thing, though, is just last week, a mother wrote to me on a post on Instagram. She said, “I'm not a wealthy person and can only afford to give $5 a month, but I show my kids that we’re protecting the Amazon.” She’s not wrong. We're not patting her on the head when we say, “We couldn't do it without you.” When I respond and say we couldn’t do it without you, I mean it.

Yes, we have large-scale donors, but we need small-scale donors. People from all over the world are contributing to protecting this place. That mother giving $5 a month is part of it. A lot of raindrops make a flood. That funding pays the rangers. That’s why they’re no longer gold miners or loggers—they’re rangers now. Because there’s money. That’s why we were able to buy the land and protect it from coca farmers—because there’s money. Those people sending that little, tiny bit—the price of a fancy coffee each month—enough of those, are helping us save this entire place. If we don’t, worlds burn.

It’s a two-part answer.

The other part is: get involved with something you care about, and help them.

There’s a really cool organization where you can restore sight for African children. Kids who are born with a medical condition that’s easy to fix. For $100, you can pay for the medical procedure. They’ve made it so you can do it as a gift: “This is so-and-so, and she can see now because, on your behalf, I gave her sight.”

I used to think I was born in the wrong time in history. We live in the best time in history. Yes, the stakes are higher. It's terrifying. But never before have more people been compassionate, working to make the world better, and never before have we been so connected—evil is seen quickly, solutions spread rapidly, and help can be summoned.

Last year, we said we wanted to protect an ancient forest—a stretch of river never cut by loggers—but we needed $300,000. We raised that in 48 hours on Instagram. One guy gave us $150,000, so he helped us halfway, but then everybody else came in—$5, $100, $1,000. People gave what they could. That’s incredibly encouraging to me.

To people who’ve never seen this forest: yes, this is important. The Amazon is crucial. If you can help, help us. We need it, and then it’ll be protected forever. We just need the help now. These are the training wheels. That will change history for this forest, for these trees, for these tribes, for all of us. We can change history.

But conservation isn’t just about rainforests or tropical places. It’s not just about rhinos in Africa. It’s also in our backyards. No matter where you live on Earth—whether it’s Tasmania, L.A., New York, Bangalore—you have wildlife in your community that also needs help.

People think of National Geographic—somewhere far away. But I guarantee, wherever you live, there's an ecosystem around you and animals that need help. Planting native plants in your backyard that help with the butterfly migrations. I now in Upstate New York, people are planting native flowers that help hummingbirds migrate from Mexico to Canada and back again, just like the monarchs [butterflies] do.

The other thing, and Jane Goodall is great on this—there’s still hope. A lot of people want you to believe it’s too late. There's a narrative out there: it’s too late, the world’s burning, let’s go to Mars. First of all, there’s f**king air on Mars. Get that straight. It’s not a great place. Next—there’s free water and air here. It’s awesome.

Hopelessness is a drug sold by those who want control. If you're hopeless, you look to them for an answer, and they sell you the next thing. But going, “Wait, wait—we’re not going to let elephants go extinct,”—that’s powerful.

There are more tigers now than when I was a kid. We went from 3,000 to 5,000. They’re climbing back up. There are bald eagles in the Hudson Valley again. They nearly went extinct in the ‘70s from DDT3. There are more humpback whales now than when I was born. I’m 37. Around 1900, they were probably down to 8,000. Now there are over 100,000 globally—almost back to pre-whaling numbers. It shows us: if you just stop. Stop overfishing. Stop ripping out entire ecosystems. Everything will be fine.

Stop annihilating the rainforest and everything will be fine. Stop murdering tigers and killing all their deer, and they'll continue to live. They're really good at it. The answer is so simple and so complex. All we're trying to do is get people to not cut down the trees.

My whole job is so stupid. My job is absolutely stupid. My job is to ask my species… I feel like when I go walking through the jungle, I look at all my friends. I see the monkeys, the birds, the jaguar, the trees. I look at everybody and I go, “hey everybody, I'm doing the best I can. I'm trying to ask my people to stop killing everything”. All they have to do is nothing. Just don't go cut down the tree.

It's like, here, you have a house. You can live in it. Then you’ve got one crazy uncle who sets fire to the house to try and cook a meal. He's like, I cooked a meal, I cooked a steak, but I burned down the whole house. Well, we have to keep Uncle Jack… we’ve got to get control of him. That part of our collective personality is out of control right now. We've been out of control for a while.

The question we are confronted with, as humanity, as a global society, is: Can we be smart enough? If we can go to Mars, if we can have this call internationally, face-to-face, even though we're not in the same room—that's incredible. Imagine with the uncontacted tribes—they would think that's pure magic. It is pure magic. We are allowed to do magic on a daily basis. It's magical.

The question we are confronted with, as humanity, as a global society, is: Can we be smart enough?

Can we convince our leaders? Can we cut through the corruption, the politics, the confusion, to see what's true and just and right and better for everyone?

That is: protect the ecosystems.

You have to protect the ecosystems because without fresh air and drinkable water, nothing else that you're interested in is going to happen. It's not possible. We rely on those things. But when you're explaining this to people, it's like: if you burn down your house, you can't live in it anymore. So, I feel like my job is terribly stupid sometimes.

INL: Many of your rangers come from nearby communities. What does local leadership look like in this kind of work—and what have you learned from them?

Paul: What we've learned from working with people in Indigenous communities is that they are incredibly open. They’re people that are learning, because they’re coming out of a lifestyle where their parents were fishermen and hunter-gatherers.

They are now a little more integrated with the outside world—the modern mainstream economy, the global economy. They own a cell phone, have clothing, and want to buy rice. They're very interested in how to modernize, improve their lives, and have better access to healthcare, maybe a little more money—so that if someone is sick, they can get medical attention. They're not people looking to get rich. They just want to make sure that if they have a sick child or if somebody breaks a leg, even if they live five days deep in the jungle, they can get them to a hospital.

So, there’s a conundrum of modernization for them. They're working toward it actively, but it’s a delicate balance. As soon as people get Coca-Cola, guns, and Jesus, it very quickly turns into a different thing. Then outsiders come in and start selling them cans of tuna. Pretty soon, they’re less and less dependent on the forest, and the forest becomes just a place they live. It becomes denatured. They’ll be more interested in getting a bigger plot of land, getting a house, and paying bills. Then they become more financially motivated.

JJ brings the clearest kind of Indigenous perspective. He didn’t have shoes until he was 13 years old. He was born onto the floor of a hut and walked around in the jungle. His dad said, “You don’t need shoes.”

There’s a meme about parents saying they used to fight dragons to get to school. Well, JJ used to walk 45 minutes through the Amazon to get to school. They lived out in the jungle, and though his community had a school, he had to hike through the jungle with his brothers to get there. He actually had to jump over anacondas to get to school.

That’s made him a really good leader. He carries the Indigenous perspective and can work with these communities. They don’t believe in linear time the way we (in Western or industrialized cultures) do. Hiring Indigenous people is its own thing. You have to work with them on their terms. You ask, “Can you show up tomorrow at 9 a.m.?” They’ll say, “Sure, of course, I’ll see you tomorrow.” But then the river rises, or it rains, or they catch a big fish and need to gut it. They'll show up when they show up. They’re like, why is time so important to you?

Meanwhile, we’re outraged. Westerners are like, “You said nine o’clock! I was ready, I had my boots on!” They just say, “It’s okay, we’ll do it tomorrow.” They have a different timeline. You have to learn to work with that.

We’re watching these communities figure out their way forward. Many Indigenous communities have done it beautifully. In Ecuador, the Waorani4 tribe has taken control of their land and is protecting it from large oil companies. They’ve embraced ecotourism—really sustainable, no motors, wealth spread equally through the community.

They’ve changed how they live off the forest, but they’ve applied their Indigenous tenets to a more modern economic way of justifying their existence. They’ve become expert guides, birders, chefs, boat drivers. It’s a smoother transition. They retain their native dignity, and that’s really cool.

The complicated thing on our river is that Junglekeepers employs a lot of the native people—but there’s a step further. What makes our river even more unique, not just in terms of biodiversity, is that we have uncontacted tribes on the river.

There are people who live in the jungle, with no communication with the outside world. They are still naked, hunt with bows and arrows, and don’t even speak to the other Indigenous communities. They’re stuck in the Stone Age—or really, pre-Stone Age—because they don’t have access to stone. They haven’t heard of World War II. They have never used a spoon. They don’t even know that water boils or that it can be frozen, because they’ve never seen it. They don’t have pots. So, they don’t know water exists in other states.

Most of us, by age two, know this is Earth, the sky is blue, there are elephants, and you learn the phases of water. It’s one of the first things you learn. They still don’t know that. So, protecting them is incredibly urgent.

They’re coming a thousand years late to modernity. They don’t know anything. They don’t know what a plane is. They don’t have clothes. They don’t have agriculture. They don’t have metal. They missed the Bronze Age. The Stone Age. They're just naked out there. They’re in the Bamboo Age, still, and they’re too scared to come out. They will be destroyed if this forest is gone. They depend entirely on the forest. Protecting them is a whole other effort. Most people hear about the expansion of Western civilization and think, “That was history.” But imagine if they hadn’t wiped out [so many of] the Aboriginal people. Imagine if they didn’t destroy the Comanches, the Cherokees, the Navajo. Imagine if we still had those strong cultures.

Think of all the pain that was caused. We have this chance to do it right. The Mashco Piro5, the Indigenous people living here, are still uncontacted in the forest. If we protect this forest, we save them too.

You can learn more about Junglekeepers here, explore Paul Rosolie’s work here, and experience the front lines of protecting the Amazon with Tamandua Expeditions here, or stay at Alta Sanctuary here.

The National Park System gained momentum in 1903 when Sierra Club founder John Muir invited President Theodore Roosevelt on a camping trip in Yosemite. Muir used the time to advocate for protecting sequoia groves and Yosemite Valley. The experience profoundly influenced Roosevelt, who went on to expand national parks and signed the Antiquities Act of 1906, laying the foundation for the modern U.S. National Park System. While Yellowstone was established in 1872, Roosevelt’s presidency marked a major turning point in federal conservation efforts.

The Bushmaster (genus Lachesis) is the largest venomous pit viper in the Americas. Its venom is primarily hemotoxic, affecting blood and tissue by disrupting blood clotting and causing hemorrhaging, pain, and swelling. Despite its potency, the Bushmaster is reclusive and bites are rare.

DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), a synthetic pesticide widely used after World War II, was found to severely disrupt bird reproduction by thinning eggshells. This caused widespread population declines in species such as bald eagles, ospreys, and peregrine falcons. Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring brought these effects to public attention, leading to DDT being banned in the U.S. in 1972.

The Waorani (also spelled Huaorani) are an Indigenous group from the Ecuadorian Amazon. Historically semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers, they inhabit a biodiverse region of rainforest threatened by oil extraction. In recent years, some Waorani communities have successfully fought to protect their territory, notably winning a 2019 court case that blocked oil drilling in over 180,000 hectares of their land.

The Mashco Piro are an uncontacted Indigenous group living in the remote Amazonian regions of southeastern Peru, primarily within and around the Manu National Park. Known for their voluntary isolation, they have traditionally resisted contact with the outside world. The Peruvian government has recognized their right to remain uncontacted, and laws prohibit direct interaction to protect them from diseases and cultural disruption.

Thanks for talking to Paul, he's a treasure. Such important work he's doing down there.