Tracking: The Language of Nature with John Stokes

A life devoted to holding the door open for Indigenous and Aboriginal wisdom.

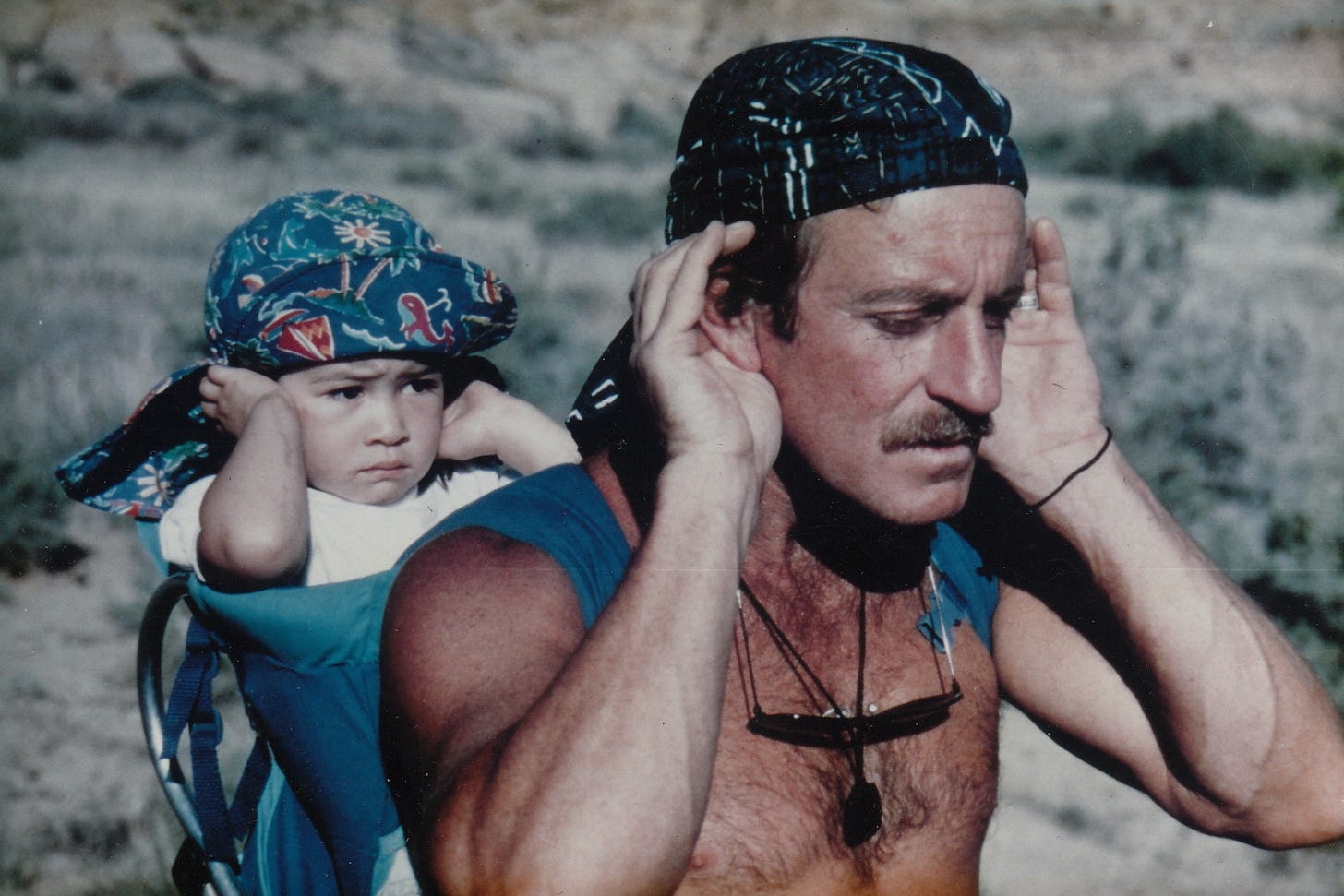

Tracker, educator, and cultural liaison, John Stokes is the founder of The Tracking Project, an initiative dedicated to preserving Indigenous knowledge and traditional ecological wisdom. With over 40 years of experience, John has collaborated with Native elders, artists, and community leaders around the world, focusing on connecting youth with elders through informal education and the teachings of tracking.

John’s work centers on rekindling the relationship between humans and the natural world by teaching the principles of awareness, observation, and respect. His global efforts, from Australia to Brazil, continue to inspire the revitalization of traditional skills, community resilience, and environmental stewardship.

This interview has been transcribed from audio, with some revised sections.

INL: Where did you first encounter Indigenous knowledge systems? Could you share how those early experiences influenced and guided the course of your life?

John: My tracking experience and my experience with Native people began in Australia in the 1970s, but I was raised in Florida, and I was born in Ohio. What has become clear through my work with the youth over so long are the formative experiences we have as young people. I remember picking up arrowheads when I was a youth. I had a deep love for nature, and I was outraged at the state of the world, because the year I was born was when Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring1. People were learning about DDT2 and the effects. Lake Erie was dead, and the Cuyahoga River3 used to catch on fire from the oil slick on the top. I was filled with a passion, and my feeling was, “What is everybody doing? Why isn't anyone doing anything about this?” So I was kind of carrying that concern: “Who's going to protect the animals? Who is going to take care of nature?” I was outraged.

Well, I moved to Florida, and it was just absolutely gorgeous. Everything around me showed me that there was a native presence from a long time ago. There were mounds and there were ruins. A friend of mine had a father who was an archeologist, and he was given the ability to go into a site before it was bulldozed to make a college. I dug there and found beautiful, beautiful things. So this understanding that there was a native presence here for tens of thousands of years was really within me.

Jumping to 2016, I took some fossil items that I had picked up when I was a kid in Florida, and I gave them as gifts to some of the priests of the Four Peoples of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta4 in Colombia. One of the elders took it in his hand and said, “Where did you get this?” And I said, “In Florida.” And he said, “How old were you when you picked this up?” And I said, “I was 15.” And he said, “You were thinking of this day then.” Well, now that is fascinating. So this idea that the seed of who we become is within us is very dear to me. When I look at each child, I see that that's what I'm helping to cultivate. It's like a pearl. It's like a jewel.

At that time I didn't know any living Native American people, but I had a tremendous respect for Indigenous culture and presence on the earth. I then got to Australia and met these remarkable people, and I heard the didgeridoo—that was a sound that captivated me, because I'm a musician—and it had this remarkable sound. I felt I had to meet the guys who do that. So I went to the community college, and I introduced myself. The person who was at the desk told me that I don't know my dreaming, and I don't know my totem. So, I said, I'm not an anthropologist, I'm a musician. I just like to play music with the people. Do they get together at any time during the week? Could I join in?

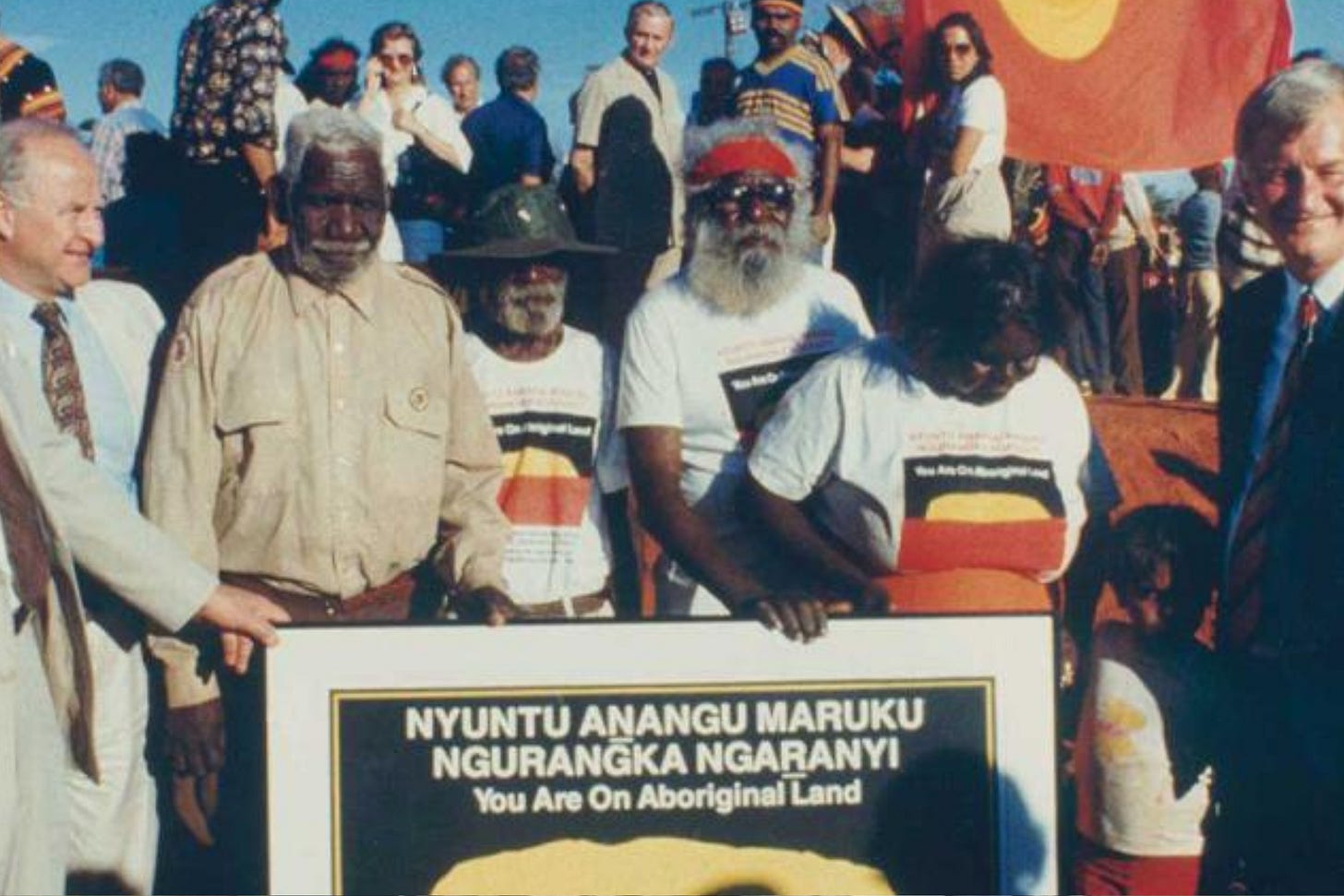

They introduced me to their tribal man, who was a very powerful and scary guy who later became my teacher. He was from The Kimberleys5, and he was very knowledgeable. He was a painter, and because of that, they called him Michelangelo (it was not his tribal name). They liked me, and I liked them, and so I became a teacher at this college. I was a country western guitar teacher. Then they realized John’s been to college, and the students like him. And so I took on more duties. Then I began working with the ESL (English Second Language) group. They were all Pitjantjatjara people6 from the Central Desert. Again, I got on really, really well with them. And so my duties grew and grew, and my chance meeting with them turned into seven years of study at a time when things were just opening up. They called it land rights—Pitjantjatjara land rights. And the idea was to get that big, beautiful rock called Uluru7 back for the Aboriginal people. It was a big deal. I worked very hard politically and got involved with all kinds of struggles and cultural issues. And I'll be darned, we did get the rock back for the Pitjantjatjara people.

Well, they didn't want only the rock back; they wanted to close up sensitive caves where they still did ceremonies around the edges. So I saw how vital that was, that the sacred sites would be returned to the people.

As I studied and worked with them, I realized there was a growing global Indigenous movement. Later, at the World Indigenous People's Council, there was a Maori guy there, and he's talking with a Seneca guy, and they say, “Oh, yeah, we got this guy, John Stokes. He's been helping us with our young guys, maybe you should give him a call,” and I was wondering, how did these Maori guys hear about me? And how did this girl from over the Arctic Circle meet this Amazonian Indian? It's because Indigenous people get together, and they share with each other. So I entered into a world that was so fascinating, and that I still am part of.

Now, here I sit in New Mexico, home to 23 living tribes, as well as the ancient ones who built giant pueblos and left behind the ruins of Chaco Canyon8. I'm very much on the ancestral and living lands of the Puebloan peoples9, and so again, this is fascinating and vital and wonderful, and they play such a role in our history. It's been quite a wonderful journey.

INL: Tracking is both an art and a science, something that is disappearing in the dominant culture. Can you speak to your experience working in the space between elders and their living wisdom, and those who are carrying on this knowledge?

John: You know it was evolutionary, the way that this came to me. I was in Australia. I was working with Aboriginal people, and studying what had taken place in Australia. One of the things that was so obvious was the vast gulf between Indigenous culture and the so-called dominant culture—the lack of understanding and the emotions, and the hurt, and the pain of their history. One of the other things that struck me was that there were words that Aboriginal people had when they first met Europeans. They had to do with this concept of ‘having eyes, but not being able to see’—to be able to look at something and absolutely miss everything. Whereas the Aboriginal people, when you see any time they're portrayed in a movie, always seem to have remarkable perceptions; magical things happen around them. Whether it's with the trees, the water, or the rain, or they'll laugh and say, “Oh yeah, we go up in space,” and it's fascinating to everybody. But they chose to live this way. They really have those abilities. So I thought, ‘Do I want to be in the tribe that can't see or the tribe that can?’ And I thought, ‘Well, I'm going with the guys who can see.’

That can just start very simply by looking at the ground. Some of the young guys loved having fun with the American. They’d look down and say, “Teacher, teacher, who made this track?” And I'd say, “I don't know.” This was just happening on an outing with the school. They'd say, “Well, what's this plant good for?” And I'd say, “Well, I don't know.” And they'd say, “Where's the water?” And I'd say, “I don't know.” And the joke was, ‘wow, for a teacher, you don't know a lot of stuff’. So they said, “You ask us to listen to you when we're in the classroom, and so when we're out here, you listen to us.” And so I did, and I picked up a lot—just little, little, little—but everything. How to see everything differently.

Then I came back to the US on a visit to see my ancestors, my elders. My grandparents were very old. I also wanted to meet the Iroquois people, and so somebody took me to a tracking school. When I got to the school, it was like magic. I realized those guys in Australia had been teaching me how to see. This idea of tracking, which is so foreign to us—that it could even be done, and not just for animals, and not for lost people, but to see as a way of being. I realized this is what I'm looking for. This is how I could give people eyes—to see—because tracking is all about paying attention.

I realized those guys in Australia had been teaching me how to see.

At that time, bless his heart, I was speaking to one of my students, and I said, “Man, wouldn't it be great if there was a tracker who was still alive?” And he said, “One of the greatest trackers of Australia lives right down the road. Let's go see him.” So we went down the road to meet this legendary man named Jimmy James, who was living in the Riverlands. He thought we were taking him on a job. So he had his little pack, and he was ready. He was very famous because he would find people when 200 men had spent a week looking for them. He could pick up the track and find them. He was absolutely incredible. I was 27, he was 72. He called me ‘old fella,’ I called him ‘young fella,’ and the two of us became a famous pair, and everybody would just laugh that the Yank was hanging around with Uncle Jimmy James. He didn’t school me; he gently taught me. He was actually training his nephew, but that nephew was in a car crash with a bunch of young guys, and they all died. So this receptacle of all that knowledge that Uncle Jimmy gave him was lost. Then everyone asked, “Who did Uncle teach?” and they were like, “Oh no, not him… not the white guy.” We continued to pal around and we were kind of a famous pair, and gradually I began to spread out, do more, and bring in more guys.

The idea of an Aboriginal tracker? Wow, that's a really old concept. Probably in the US, we haven't seen such a character for a couple hundred years. Yet most Native people are good trackers because they live on the land, and it's important that you notice the signs—whether it's the signs of the weather, or whether it's the signs of the thing you're after on the trail, or how the fish are doing in the river. There is an idea that the trackers were actually the trainers of the youth because they taught everyone how to see, in a good way.

The old people used to say, “Uncle Jimmy can track a fish underwater.”

So I took tracking back to a time that I was reminded of and told about. In that way, tracking became my thing, and the idea is that tracking goes together with survival skills: fire-making, shelter-building, wild plants—because the tracker likes to travel light. You don't have a backpack. You just put a little bag on your side. You’ve got a little bag of chia seeds around your neck and off you go, because you're following things over a fair distance. So you want to travel light, you want to know what you're doing, and you want to be able to answer all your physical needs as you track. So the two go together: tracking and survival.

My goodness, the young people adore learning skills that help them. They realize that you sense their well-being is important. You're giving them something very valuable. At the same time I was starting with this work, there was more and more talk about “attention deficit disorder” and they were sending me kids who couldn't sit still. Well, they could sit still when they were listening to me, because they realized I was giving them something valuable. One of the things the young men used to say was, “Uncle, you gave me a toolbox to fix my life whenever anything was broken.” And how cool is that?

INL: How do tracking skills reflect deeper cultural and spiritual connections to the land?

John: There's a concept, and it's spoken of sometimes. I think if you were wise, you wouldn't even want to try. It's this concept of the Dreamtime10. There are all kinds of names for it, and it may not even be a good term. I think when they were asking the Aboriginals, “How did all this come to be?” and they described what they believed, the white man said, “Oh, kind of like our concept of dreaming.” And so it just stuck. But that's not it. There was a time, a creative time in the past, and it was when things were created.

These ancestral beings came up out of the earth, and they moved about, and they did things, and these are the stories that remind us of those things. When the Dreamtime ended, they either went back into the earth, or they became odd-shaped rocks or a mountain range. You have these in other countries too. It's just that the Aborigines became famous for it. If you go to Hawaii, there's lots of natural form that has stories—that have to do with Pele11, or that have to do with other cultural heroes.

The idea (from the Dreamtime) that when the rainbow serpent went along and did this (winding) and left a waterway or a river, you can see that that's the same as looking at the track of a snake today. And where somebody dug for their boomerang, there's a big hole there now. There's a connection between seeing the landscape as tracks and the tracks that are actually there on the ground.

When you get into tracking, it's very truthful. You don't make up a story and say the thing did this, that, and whatever. It's all about the truth. Native people, especially Aboriginal people—why would they make up a story that wasn't true? It doesn't benefit anybody.

If we remember the stories from the beginning of time, we remember what we were told to do and not do. We keep the creative time alive. And if we do that, we assure the future, because we're in line with things as they are. The tracking that we do on a daily basis keeps us in line with our past, with the Earth, and with the future of the Earth.

Now, we go to the petroglyphs or the paintings on the wall. They can be tracked too. A simple example: tracks on the rock wall of the two front hooves of a deer. First note, when a deer bounds, they lower the back of their leg, and you actually get to see further up, all the way to their knee. They push off of the whole lower leg—that's the gait that that creature uses when they run. But that petroglyph doesn't mean deer. The deer is depicted as running. It means at this place, the people had to run to escape.

So, there are cues all over the world—all over the rocks and everywhere else—to be read, to be tracked. Once you start to see tracking in this bigger perspective, you realize that you could be tracking the landscape, whether it's the geological history of an area, whether it's how the Native people arrived at that place, or how they came to that continent. It's all tracking, paying attention, reading the signs. When something goes left, there's a mound to the right. It's an equal and opposite reaction. Tracking are the principles that we all know about, that we would call physics, all worked out right there on the ground. And you can study it. So it’s very, very deep.

INL: Can you speak to the idea of non-Indigenous allies, and what role we have in supporting the protection of native territories and revival of living wisdom?

John: You know, in my time and history with the Indigenous people, the Aboriginal people, I learned very early to only go where you're invited. And don't do something just because you think it needs to be done. You need to be asked, and you need to have permission. There's another world that's kind of unheard of, and it is giving credit where credit's due, and only going where you're asked to go. So when the Aboriginal elder asked me to help, it wasn't a request. It was put to me as a responsibility. And there were rules given to me which I think are important, and it was, ‘I'm gonna give you this, but it's not for you, it's for the ones who are gonna come to you. Don't be stingy, be generous like I was with you. And where you see the door closed to Aboriginal people, go in and open it from the inside for us.’

I believe that any non-Indigenous could be a carrier of a feeling about Indigenous people that could open the door for them. In a place they might not even be in the room, but you may hear people who will say silly things, and you enlighten them, and say, ‘Well, that's not at all how it is. Have you ever read this? Do you know that?’ So we can all be agents of a more truthful look at who we are as people.

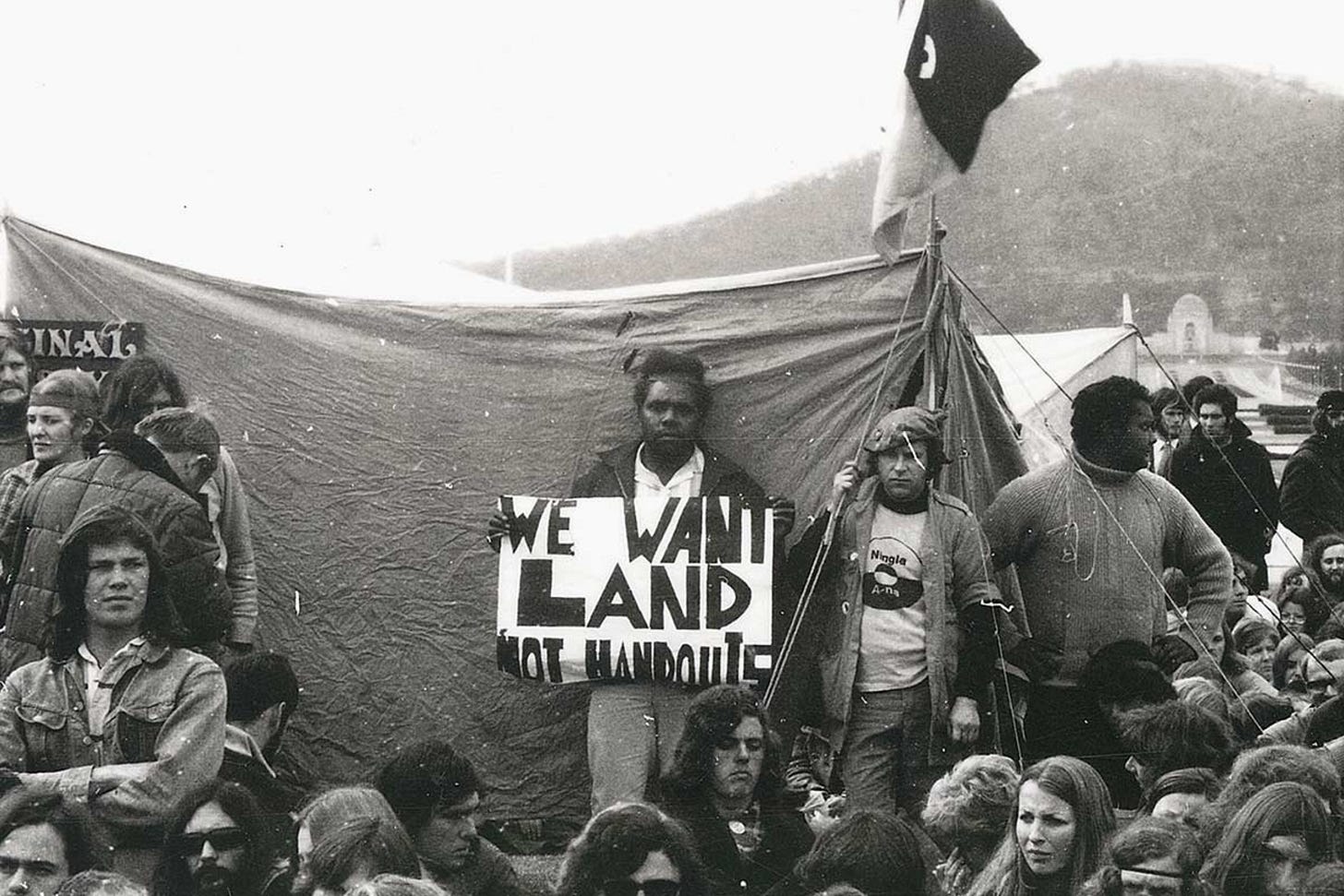

We can all see that Indigenous people have been very poorly treated—not just for a year or two years. There are actually Indigenous people coming to the Iroquois from Africa, and they're asking, ‘How did you guys survive 500 years of this?’ Because they're not doing well. I've been in the gathering. They come from Botswana, and they come from Namibia, and their tribal elders sent them to find out, ‘How did they do it?’

I often say to people, one of the things in the future that's going to be incredible to everybody is—how did the Indigenous people survive? This onslaught? That somehow you could go to another land and butcher the people and take their land. It was unheard of.

There used to be people who would come to Australia to interact with the Aborigines. They were Macassans12, and they would share their culture, and they would live with them. They were from Indonesia. Then they would sail away, and it was always sad for the Aborigines to say goodbye. No one came and tried to stay there, and take their land.

So all of us could be an agent of more understanding. You could always be there to bulk up the crowd if they're asking for some people to ‘come and support us.’ You could do it physically, you could do it mentally, you can educate yourself as to what really happened here. I would say to everybody: you're gonna get sad, but you should look at the history of your state. Look at the history of your county, and see what happened. See if there's anything you could do, to make it a better place.

Look at the history of your county, and see what happened. See if there's anything you could do, to make it a better place.

I can go on and on and on. But imagine they want to bulldoze the petroglyphs here that are the record of the people of the last three to four hundred years. You just go to the meeting and stand up to prevent that from happening, because the Indigenous people, they're not in big numbers; they're just very brave, and they're very clear about what they want, and you could always stand with them. Those are safe things to do. Of course, what people are trying to do is get the feather and get the song and set themselves up as shamans, and that's not necessarily helpful at all.

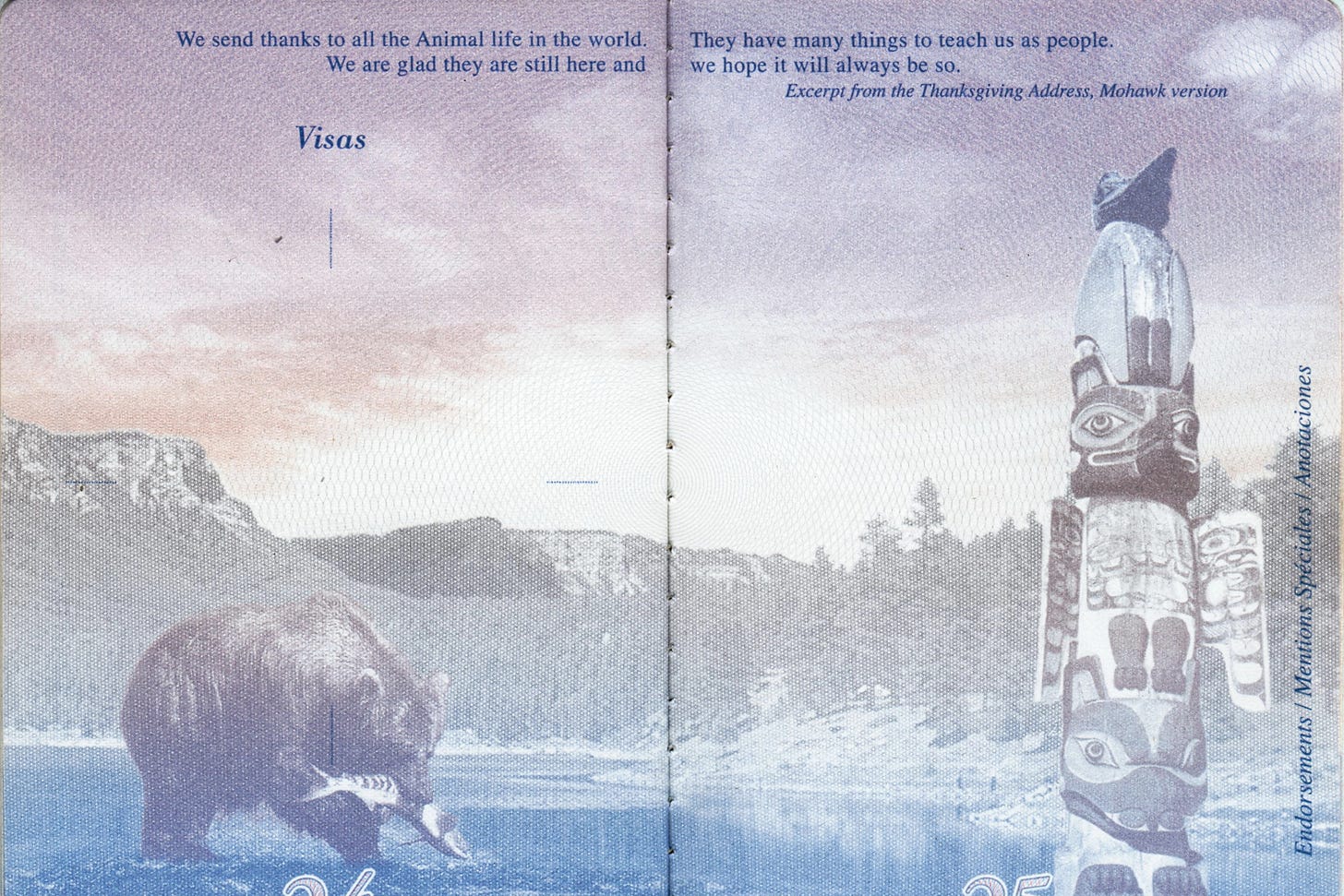

INL: You published the Thanksgiving Address in 1993, a spiritual address that is used to open gatherings across original nations. Can you explain what it is, and speak to the collaborative process?

John: Well, I shall try and be as brief as I can. It's a terribly grand story. The so-called Thanksgiving address—those are English words to describe something that the Iroquois people call the opening—the opening words. In Mohawk, and I think I'll say this right: Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen, which translates as the words we say before we do anything important.

Now imagine that before we start a meeting, before we start a gathering, before we start a dance, or a cultural event—someone stands up and says the address—to address all the things here on the earth that make our survival possible.

We have a tremendous capacity to forget what is keeping us alive. And if you go too far, you're going to have an elder saying, ‘How could they just destroy the very thing that assures their survival?’ Well, it's because they forgot. But, you don't forget if you say it every day, right?

So the human climbs this ladder, and the ladder is set on Mother Earth because she supports us. And then up you go, up this ladder, and you send your greetings and your thanks to each thing as you climb. And so it has a format (each element mentioned in the address builds upon the previous one, leading to a higher understanding of our relationships with the Earth and each other). The format is not rock solid, but it'll be agreed upon. There'll be Senecas saying it a little bit different from Onondagas, and Onondogas saying it a little bit different from the Mohawks. But they're all within the Iroquois Confederacy13, or Haudenosaunee, the longhouse builders, which they began to call themselves after a man called the Peacemaker came and united them under one roof.

It's a tremendous history, and It'll take you pretty much most of this life and into the next to study them. They've been around for a long time, and those words are so moving and so important, they actually say that when they forgot them, their world fell apart. And when they remembered to come back to them, their world came back together. It's horrible (and you see it all around you) to forget nature.

We all love to quote Einstein about the bees14—that we would last for four years. Is this sustainability? That's a model of sustainability? Well, obviously, each thing in the web of life is interrelated with all the other things within the web of life.

So to the tracker, to the Indigenous person, the web of life is very real. It's not a poetic concept. It is a way of saying what you see, but that is reality. So here you go, and we say these opening words. And there's something also very important. It's a call and response. So when the speaker says, ‘We now turn our attention to the waters of the world. They give us life, they convey vitality around the planet. We could not live without water, so let's send our greetings and our thanks. Now our minds are one.’ And the people respond, Aho. ‘I agree.’

And so you not only are reminding yourself of the importance of nature, you're actually creating unity within the people there that day, that this is what we all believe in. Now imagine, that's not the end of your meeting, that's the beginning. Imagine where you can go when you're united with others.

I heard Chief Oren Lyons15 speak those words at the Earth Mass with musician Paul Winter in a cathedral in New York City, where I was invited to play music that day, and it changed my life because I had always wanted to hear someone thank nature.

I had always wanted to hear someone thank nature.

Now, that went on for some years, that I would just say to people, ‘We talk about humans, and we talk about God, but we don't talk about everything in between.’ How could you forget nature?

In 1990, Chief Jake Swamp16 said to me, ‘You've been around, you've heard the opening, we think you have a good understanding. Would you write a version of these words in English for the rest of the world to know about this?’ And of course, I was terrified to mess with somebody's original instructions that come from the beginning of time that they cherish.

So I took my time and I wrote it.

I was working with Mohawk artists and I was working with the leadership, and I would write a version and then I would submit it to them. They would read it, and say, ‘Okay, this is pretty good.’ We then had to decide on the format, and I was given the printed version of every one that anyone knew, and I was to take those and then assemble them and put a spin on it of my own. There were certain things that needed to be included. And there was one chief who asked me to take one thing out. He said, ‘You know, Mr. Stokes, this one's very close to my heart, and I'm not really ready to share it with everyone.’ So we took it out. Then there was on the team a brilliant Mohawk speaker, whose name is Rokwaho, and he translated what I had said into Mohawk. But then he would say, ‘You know where you said this, John, we don’t really say that in Mohawk, so I said this because that's the closest I can think of.’ And I said, ‘Oh, well, how does that translate?’ And he said, ‘It translates as this.’ So I changed my translation to meet his translation. And then when we had done all those changes, and everybody had read it, and everybody had signed off on it — they sanctioned it.

It has drawings by a wonderful Mohawk artist, Kahionhes17. It was the translation by Rokwaho. There was English up the top. We all agreed as a team. So pretty good — but then Jake Swamp said, ‘I want you to translate it into all the languages of the world.’ So that when people get together, especially the young people at a gathering, and they say, ‘Would one of you like to do an opening?’ and one of them stands up and does Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen, all the others would say, ‘Oh, that's the one I was going to do.’ And they would find themselves united.

So we decided to change the top language, but we will always keep the Mohawk there as a reminder of its origin.

We also copyrighted it, and we did that because I said people are going to buggerize this thing. They’re going to cut this, they’re going to stop that, they’re going to read it from the back to the front, they’re going to try all manner of stuff, and we need to retain some power. So we copyrighted it in the name of the Six Nations Indian Museum and the Tracking Project because we want you to keep it like this. This is the way it's supposed to be.

INL: The Tracking Project has worked across many Indigenous communities worldwide. How do tracking techniques differ from culture to culture?

John: Nature is such a vast area to study. The tracking techniques of a culture are indelibly linked to where they live. The techniques of a Zuni18 might not differ too much from a Navajo19, but if we were to go up over the Arctic Circle to people who are moving in the snow, they're going to have a really different take. Coastal people are not only people of the mountain, but they're people of the sea. So wherever you go in Africa, or on the coast of China, Japan, or Australia, the people who live near the water can track the ocean, and they can track the up-country.

The people in the forest don't get a line of tracks like the Zuni might get in the sand. And so what they do is called sign tracking. They more track a sign — a bent twig, one track, a scat pile, a feather, a cut, a bed where the animals lay down. So you find different levels of tracking based on the terrain and the creatures. In our realm, the idea that you can read the ground, the idea that there's a manuscript written there — not many people have been shown how to read that language.

We don't have to go so far. We can track our breath. You know, the way that somebody breathes has got a whole lot to do with their awareness and their attention. Seeing how somebody stands, tracking their posture, tracking when somebody comes into a room, the things that they do when they enter the room, where they sit in which direction, this is all tracking; it's taking notice.

The other day in a meeting, there was a woman from Sweden, from the Sami Nations. They track wolverines, bears, wolves, and reindeer in the snow. They have a very different level of skill than what I am used to.

Additionally, I’ve worked with Hawaiians who practice a system known as wayfinding. The wayfinder navigates a canoe without any instruments, traveling thousands of miles across the ocean and arriving on a little beach on an island far, far away. They can even read the slap of a wave on the prow of the canoe.

There are elders who can taste the water and say, "We're getting close to Fiji." There's a whole range of skills of reading the clouds and the birds. You see one bird, and it's like, "Don't follow that guy." Oh, he might be going back to land. No, he's going to Aotearoa. Or he's on his way to Tasmania.

So, there's a whole body of knowledge that goes with each place on the earth.

INL: Can you elaborate on the body of knowledge that accompanies different places on Earth and how it influences your work?

I began thinking, why don't we put tracking together with wayfinding and then we would have a curriculum for planet Earth? And there are some people who are looking into that. But the idea is to go into a community, show people that the knowledge they have is valuable, and encourage them to come together with the kids to start sharing it again. That's what I do: I jumpstart the process of bringing the elders and the youth back together — because the ways that elders and youth used to come together have been destroyed — and I aim to restore that through informal schooling.

Formal schooling has a building, a curriculum, materials, a clock, and a teacher, and time. Informal education has no school, no building, no materials, no clock, and school begins when the elder speaks — and you listen, you pay attention. They teach with stories and not with lists. It's very different.

At the Tracking Project, in the beginning, the kids were paying me by selling popcorn balls and giving me gas money. While people often talk about the youth and how important they are, you don't really see it played out when you're an educator, and kids are kind of shunted to the back. So, I realized I was doing a good thing. The elders enjoyed it. The kids enjoyed it. I knew I’d have to go non-profit to get the funding to pay myself to continue this work.

The Tracking Project will be 40 years old next year — that's a long haul. We’ve taught so, so, so many people, and I'm super proud of what we've done. We now have a vast family of men and women all over the world who are community educators and community activists.

I very much believe in artists as the conveyors of the vision.

Our people are artists.

You can learn more about John Stokes and The Tracking Project at TheTrackingProject.org and you can order the Thanksgiving Address: Greetings to the Natural World here.

Silent Spring, published in 1962 by Rachel Carson, is a seminal work that highlights the dangers of pesticide use, especially DDT, and its detrimental effects on the environment and human health.

DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) is a synthetic pesticide that was widely used after World War II to combat malaria, typhus, and agricultural pests. It was banned in 1972 due to its environmental and health impacts.

The Cuyahoga River in northeastern Ohio, flowing through Cleveland into Lake Erie, is historically significant for its role in the environmental movement. It became infamous in the late 1960s when it caught fire due to pollution, notably in 1969, which highlighted the severe industrial waste issues and led to the establishment of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Clean Water Act.

The Four Peoples of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in Colombia refer to the Kogi, Arhuaco, Wiwa, and Kankuamo Indigenous groups. These communities share a rich cultural heritage and inhabit the Sierra Nevada, which is one of the highest coastal mountain ranges in the world.

The Kimberleys (or the Kimberley) is an ancient landscape in Western Australia and one of the world's most precious wilderness regions covering hundreds of thousands of square kilometres. Aboriginal traditions, stories, and knowledge play a vital role in the stewardship and preservation of the Kimberley’s unique environment.

The Pitjantjatjara people are an Indigenous Australian group located in the Central and Western Desert regions across the Northern Territory, South Australia, and Western Australia. In the 1980s, they significantly contributed to land rights movements, resulting in the return of their traditional lands under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976.

Uluru, also known as Ayers Rock, is a massive sandstone monolith located in the southern part of the Northern Territory in central Australia. It is one of the most iconic landmarks in the country and holds great cultural and spiritual significance for the Anangu, the Indigenous people of the area.

Chaco Canyon is a significant archaeological site located in northwestern New Mexico. It was a major center of Ancestral Puebloan culture from approximately AD 900 to 1150. It was likely a political, religious, and economic hub, facilitating trade and cultural exchange across the region.

The Puebloan peoples are Indigenous peoples of the Southwestern United States, primarily known for their unique adobe and stone dwellings, often referred to as pueblos.

Dreamtime refers to the Aboriginal Australian concept that encompasses the spiritual, cultural, and historical beliefs of Indigenous Australians regarding the creation of the world and the ancestral beings who shaped it. It represents a timeless realm where ancestral spirits journeyed across the land, creating landscapes, flora, and fauna, and establishing the laws of existence. Dreamtime stories are integral to Aboriginal culture, conveying moral lessons, social norms, and connections to the land.

Pele is the Hawaiian goddess of fire, volcanoes, lightning, wind, and dance. She is a central figure in Hawaiian mythology and is considered ʻohana, or family, by many Hawaiians.

The Macassans were seafaring traders from the Indonesian island of Sulawesi who established a trading relationship with the Aboriginal people of northern Australia.

The Iroquois Confederacy, also known as the Haudenosaunee is a political alliance of six Native American nations: the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora. Renowned for their sophisticated political system, the Confederacy played a significant role in shaping democratic principles in North America. The term "Haudenosaunee" emphasizes their cultural identity and communal values.

The quote often attributed to Einstein about bees is: "If the bee disappeared off the face of the Earth, man would only have four years left to live."

Chief Oren R. Lyons is a traditional Faithkeeper of the Turtle Clan and a member of the Onondaga Indian Nation Council of Chiefs of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, or the Haudenosaunee.

Jake Tekaronianeken Swamp was a respected leader and Mohawk from Akwesasne, New York who served as a royaner for the Wolf Clan for 30 years.

John Kahionhes Fadden was an Akwesasronon artist and educator. His work depicts Haudenosaunee culture and history.

The Zuni are a Native American people primarily based in the Zuni Pueblo in western New Mexico, near the Arizona border. The Zuni are known for their deep cultural traditions, religious practices, and distinctive language, which is unrelated to any other Native American language.

The Navajo, or Diné, are one of the largest Native American tribes in the United States, primarily residing in the Four Corners region where Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado meet.