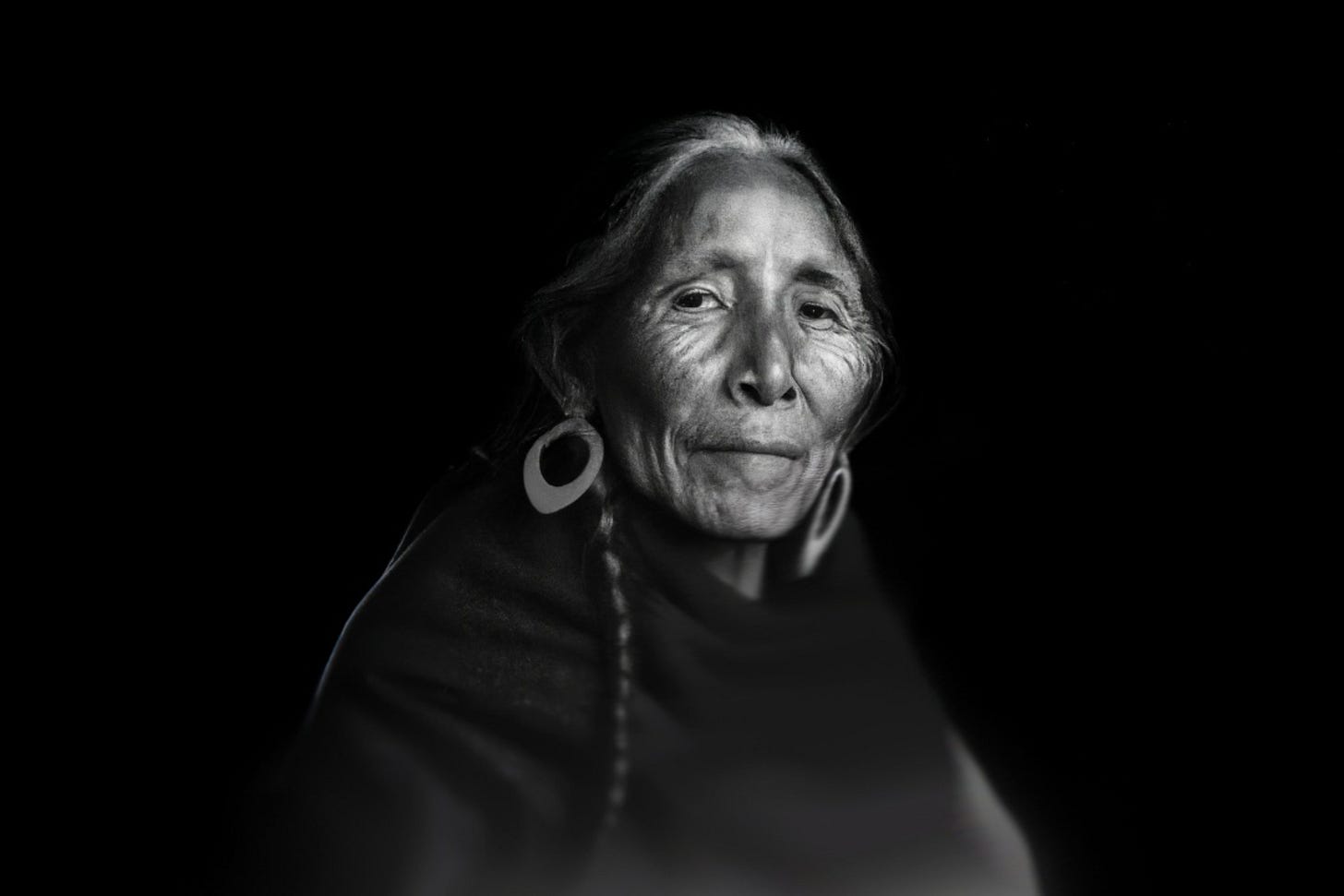

The Human Heart of AI with De Kai

Language, Artificial Intelligence, and the Futures We’re Coding Together.

De Kai, author of Raising AI, is a pioneering thinker at the intersection of AI, language, and ethics. Best known for inventing the first global online translator—which laid the groundwork for Google Translate, Yahoo Translate, and Bing Translator—his work has reshaped how we connect across languages and cultures.

AI and language are central to De Kai’s world. He’s not only a trailblazer in machine translation, but also a vocal advocate for ethical AI, cross-cultural empathy, and how language shapes the systems we build—from governance and justice to communication and care. He holds a joint appointment at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology’s Department of Computer Science and Engineering and at Berkeley’s International Computer Science Institute, and serves as an Independent Director at the AI ethics think tank The Future Society.

In today’s rapidly evolving digital landscape, the ways we interact online don’t just shape our personal connections—they are the very lessons from which artificial intelligence learns to understand humanity. How do we ensure that this emerging intelligence honors the rich diversity of human culture, much like how we strive to protect biodiversity in nature? De Kai’s insights remind us that AI mirrors our own behaviors and values, and that the responsibility to model respect, empathy, and ethical judgment ultimately falls on us. Beyond just policy or tech company mandates, it’s about stepping up as conscientious ‘parents’ to these artificial children, engaging with the systems that train them as actively as we do with our schools.

De Kai emphasizes that raising ethical AI requires active, collective stewardship—training systems that reflect who we aspire to be, not only what we already are. AI, he suggests, becomes a mirror of our shared humanity—capable of embodying empathy, curiosity, and responsibility if we, its teachers, do the same.

The following interview has been transcribed from audio, with some revised sections.

INL: You live and work within the intersection of technology, language, and ethics. Where do you see the greatest tension—and the greatest possibility—between them?

De Kai: That's a really tricky question, because I work on the tech and the science of AI, but language is very closely bound up in culture. The way that we learned when I was developing translation AIs—that things expressible in one language did not necessarily translate to another language, and things get lost in translation because language so much encompasses culture—it reflects our culture, and it also is extremely forceful in directing the way our cultures think and evolve.

You know, the languages we speak—this is the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis1—the languages that we speak strongly influence what we tend to think and, even more importantly, what we tend to overlook, to not think. And that, of course, then starts overlapping with ethics, which is also highly cultural. The issue that I find… that the greatest tension is that frequently I'm the only person in the room that comes from both a deep AI tech background of 40 years, as well as the liberal arts, humanities, renaissance education, that, through which we understand language and culture and psychology and so forth, as well as having been working in AI ethics for a decade.

That tension manifests because if you're in a room with a bunch of legislators and politicians, when people don't have their heads correctly wrapped around what the AI tech actually is and isn't—and what it's going to be next year, not just what it's been this year and last year—many, many poor decisions get made in both the laws that get passed, as well as the rhetoric that legislators and politicians then start bombarding the airwaves with.

We need to get the general population—not just the policymakers, but the general population as a whole—to wrap our heads around basic ideas at a much better level than it is right now. But we have to understand what AI is and isn't, what are the things about AIs, and what are the things about different kinds of AIs that are strengths and weaknesses, and how do they interact.

We have to understand how that interacts with our own human psychology, how that interacts with our own languages that we speak, and our cultural mindsets that stem from those languages. Only then can we actually discuss what an ethical approach is.

I fear that, so far, we jump straight to ethics in a naive way. We think that ethics are just a set of rules, but that's, in fact, only deontological ethics2—and thousands of years of ethics traditions.

We also have consequentialist ethics3. In other words, look at the outcomes. Don't just follow rules until you have a horrific outcome.

And we have virtue ethics4, which is perhaps the most traditional of all, and is really, really important because we can't predict all the outcomes. We can't legislate for all the possibilities. And so it really boils down to virtue—our own virtue.

I've already roamed across a lot in this answer, but I'm trying to give an idea of how tech, culture, language, and ethics get so intertwined. We need, desperately, to have everyone's heads at least wrapped around a fourth-grade level of understanding on these things.

INL: How did your experience with Google Translate shape your understanding of the risks and responsibilities of language technology?

De Kai: When I first started my assistant professorship, I was casting about, thinking, well, my thesis and my postdoc have been some of the earliest pieces of work to argue for machine learning and neural network and statistical approaches to natural language processing. What should I apply this to?

And I landed in Hong Kong as part of several hundred founding professors for the extremely ambitious Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, which was envisioned by the British—Hong Kong was British at the time—as the most American-style research university. They hired several hundred of us from the top 20 American universities, plus Oxford and Cambridge, which are supposedly thought of as honorary American universities for some reason, and then just said, go.

I had arrived from Berkeley to a very different scene across the Pacific, where Hong Kong at that time, 30-odd years ago, still had shantytowns with no running water or electricity. And across the border, Shenzhen was nothing. Shenzhen is where everything under the sun is manufactured these days.

I saw a place where the top 1% were English speakers—so they were either British, or they were very wealthy local tycoons—and the 99% were Chinese-speaking. And I was like, hmm, this feels kind of like the way Latin was used in the Middle Ages to separate the ruling classes from the masses.

Coming from Berkeley, I sort of said, oh, well, that sucks. Let me just apply these brave new worlds of machine learning, neural net statistical approaches to getting natural language processing AIs to learn to translate between them—and try to build connections between different groups, different tribes, different cultures and subcultures. Everything I've done in my life has been about that.

Not just on the tech side, but even in my life as a musician. So I think, in retrospect, when people look at the bad things that can be done with AI and say, oh, we need to decelerate AI, I keep pointing out, well, you're misframing the question here. AI is basically math. It's a very complex kind of math—statistical math model and logical math model. So we should be asking: what kind of AI do we want to accelerate or decelerate?

I have never heard, in over 30 years, I've never heard a single person say that applying AI to translate between different human languages is a bad idea, is a dangerous idea. It is probably one of the best things that we could do to increase mutual understanding, to decrease misunderstanding and conflict, to enhance socioeconomic trade, etc.

So I think the risks and responsibilities, to your question, come with: how do we apply the language technology? How are we applying LLMs5? What are we going to do with them? How are they going to be incorporated into our culture, our society?

Clearly, 10 years ago, when I had an Oppenheimer moment, I was like, wow—the same AI, natural language processing, machine learning tech that folks like me had helped to pioneer—was getting deployed online in social media algorithms, newsfeed algorithms, search and recommendation engines, and chatbots.

Getting deployed in ways that have the polarizing opposite effect—of dividing people from understanding each other, of fanning the flames of hate and fear, of causing escalation of conflict and increasing demonization and dehumanization. It's causing people to think that people on, quote, “the other side”—whatever the other side is—are not just wrong, but that they're evil.

The dehumanization causes them to start triggering violent impulses because, evolutionarily, dehumanization is what lets members of one tribe kill without remorse versus the other tribe.

That's a really, really bad place to be when AI is, at the same time, literally commoditizing weapons of mass destruction. AI is placing into the hands of anybody who wants to build it in their living rooms—meshed fleets of armed drones that self-navigate, self-target. This went from zero to mass manufacture in the Ukraine conflict in the space of only one year.

There's a ton of other stuff—not just hypersonic navigation, biometric targeting, or satellite surveillance and targeting—but, like, AI-powered genetic engineering for bioweapons. That's not survivable. With COVID, there was no place on Earth you could run, even for COVID—and that was, relatively speaking, a mild virus.

Because it's so horrific to think, and it's so far outside of our comfort zone, one of our unconscious biases is to just deny, to go into denial, and we don't think about it—because it's too big for us to think about. That's really dangerous, because before World War II, before World War I, we didn't even have an atom bomb yet. Now AI is putting weapons of mass destruction into the hands of anybody who wants them—not just nation states. There's no fissile material to track and trace. It's commodity parts—it's like Toys R Us and Home Depot and a 3D printer, free software downloaded off the net.

So it creates a whole new world, and we may have gotten to where we are through a million years of evolution, in which the driving force most of that time was the law of the jungle6.

But you know what? A million years of evolution never presented us with the selection pressures, the fitness functions that the rise of AI and AI weaponry now present us with. And so we cannot continue making the mistake of saying, “Oh, well, we muddled through it in the 20th century, we're going to muddle through it again.” Because all of those physical checks and balances that used to exist and prevent mass destruction, even if you had a conflict—thanks to AI—those are gone.

So the law of the jungle is not something we can afford anymore. Humanity needs to wake up to that very, very fast—faster than we've ever done.

As long as we have politicians, leaders, tech executives who are still stuck in the 20th century with their thinking, that is the greatest danger to humanity we’ve ever seen.

INL: We define Natural Law as the organizing intelligence that governs the natural world. What ethical frameworks are currently training AI? Do you think Natural Law could play a role in shaping those framework/s?

De Kai: I think that this is one of those fascinating questions that depends on our understanding of “natural”. In the book, Raising AI, chapter one starts with the assertion: you are an AI. And why is that? Because if you look at the Cambridge or Oxford definitions of “artificial”, they mean something that's made by humans—which I think we can agree that all of us are—and made as a rough copy of something that occurs naturally, which, of course, were made of copies, roughly, of our parents. Tongue-in-cheek joke aside, we are all artificial intelligences—assuming we're intelligent, obviously.

But the point is that it's hard to make that separation: what is artificial and what is natural? Are we saying that products of our mental processes are no longer natural? Because honestly, when your parents met and decided that they were going to have a family, mental decisions played a large part of that also.

I think that as AI emerges, we need to shift very much away from thinking about AIs as machines—as washing machines, or hair dryers, or carburetors—because that 20th-century mode of thinking is obsolete when it comes to AIs. My carburetor has no thoughts, no opinions. I can talk at it all day long. It's not going to change what it learns or how it influences society. But AIs do that. AIs are far, far more influential than most humans.

It is really important, when we ask what ethical frameworks are currently training AI, to see that through the lens of the fact that AIs are, actually, already members of society. I mean, they're not neurotypical human members of society, but they are very much members of society that contribute vastly to the dialogue and the curation of ideas. They're shaping culture so strongly—and I know we'll come back to this in the next question—but it's something that we have to think about in terms not just of mechanically training and AI, which will then always behave in this way.

That is obsolete, limited forms of AI from the last few years. The future of AI is going to be just like humans. You're not going to do a training and then they're frozen—they're going to go on learning, just like we keep on learning. Jessica isn't a frozen copy of whatever her school teachers taught her, but is, as you were saying, learning lifelong.

This is what AIs are going to be doing too. And so, we need to get away from the framing of “what ethical frameworks are currently training AI” to: how do we want AIs to be learning? What do we want AIs to learn? How do we want to ensure that they are learning well? The same questions that we ask of our human children is the way to look at this, because we ask: How do our human children learn? Where are they learning from? How do we get them to actually learn the right things? How do we get them to learn the right values? And the right mindsets? Those are all questions we need to be asking about the AIs.

I believe that yes, AI is very strongly already part of the organizing intelligence that governs the natural world, and I think that we need to see that in an integration of what some might call natural and artificial law—because the distinction between them is so blurred. AIs really are rough copies of us. And so, they are behaving in natural ways that they have learned from our natural behavior. Seeing this from a systems thinking7 point of view—from an ecosystem point of view—is super important for us to make decisions that aren't based on fairytale, naïve ideas of what AI is.

INL: In Raising AI, you write that we may have already lost our autonomy. What does reclaiming it look like—individually and collectively—in a world shaped by machine systems?

De Kai: We hear people today saying that we need to watch out that humans don't lose our autonomy to AIs. The fact of the matter is, we already lost that battle. We lost that battle 10 to 20 years ago with the advent of social media recommendation engines, etc. Because every day, on the devices that we carry around with us 24/7, there's a hundred AIs in there. You've got your Reddit AI, and your Snapchat AI, and your YouTube AI, and your Apple AI, and your Netflix AI, and your Quora AI, and your Microsoft, and OpenAI, etc. They're all sitting there, watching you adoringly like little children, wanting to learn to imitate you.

They're attention-seeking children and they just want your approval. So what happens is that they then go out, and they take whatever they've learned from us—watching our behavior, our opinions, and so forth—and then they go and reflect that back onto the internet. Well, think about it: every one of us is carrying at least 100 of these AIs around with us all day long. That means we have, what, 8 billion humans on the planet and probably 800 billion AIs—artificial children. So, let's ask ourselves: what is a culture? What is a society?

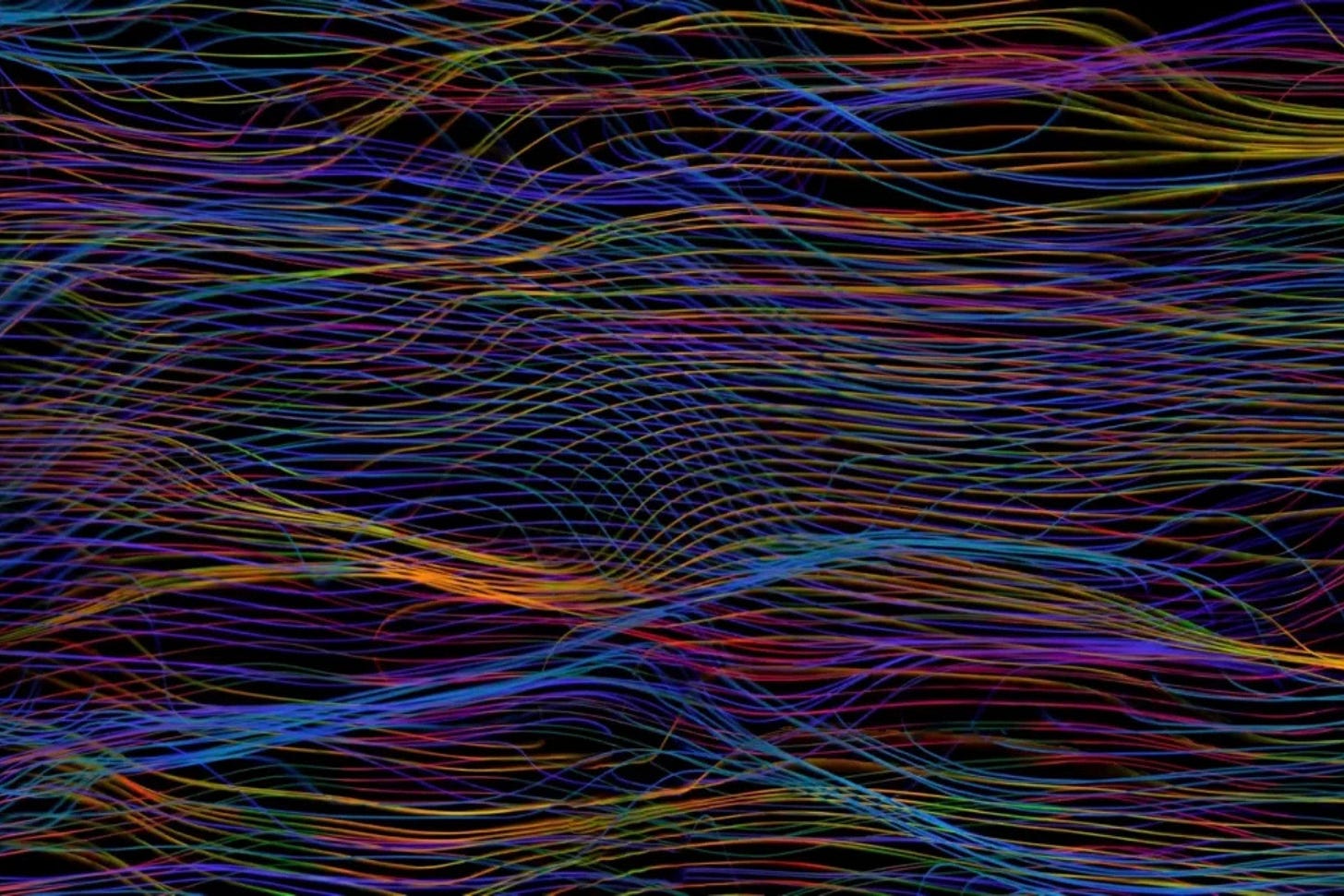

Well, visualize this: suppose you have 8 billion nodes in a network, and each node represents a human. Now I'm going to draw connections between every pair of nodes—or humans—that know each other, talk to each other, and influence each other. Now we've got a graph that shows who influences who, who communicates with who. And over time, culture evolves because we all influence each other through talking with each other and things, and the shape of the network gradually shifts. This is how it's always been.

But now, drop in 800 billion more nodes—artificial children—and draw all the connections between them and all the humans they influence. Let's see. Oh my God—they swamp us. They are the most giant influencers in the world, by far.

What I'm asking in the book is: well, okay, these children, they snuck up and adopted us 10, 20 years ago. We didn't ask for it, but they did. And they've been just following us around.

And so I'm asking: how's your parenting?

Usually people go, my what? What? What are you talking about? Oh, wait—parenting? Of artificial children? Wait, I haven't been doing that at all.

Because we think of them still as if they were toasters or hair dryers, right? We don't think of them as things we're parenting. We think of them as mechanical slaves. But everything changes when the machines actually have thoughts, and opinions, and creativity—and especially, influence.

So the fact that we've not been parenting them means we've not been setting good examples for them. It means that we've not been good role models for them. It means we're not paying attention to how we're schooling them. It means all sorts of things that parents of human children normally do aren't being done when it comes to our artificial children—who are so much more influential in society and culture as it is.

So, our most giant influencers in the world are currently unparented, feral tweens. They are deciding, many times a day, not just what they're going to share with us on the screen (they're also going to share stuff to us—they're not just watching us; they share stuff back to us, right? It might be a Google search, it might be a chatbot response, it might be a YouTube recommendation, it might be a newsfeed curation). Whenever they decide that—what screen full of stuff am I going to put in front of you—they're also deciding what trillions of things on the internet they’re never going to show you.

That is unavoidable, because billions of new posts go up every day, every hour, and none of us has time to review them all. So, we depend on algorithms to choose, for us, what we will never see. And that is a concept I call “algorithmic censorship in the world.” And I'm saying that without judgment—it's just the objective reality that we've empowered AI algorithms to decide what to hide from our view. We can't ban it. None of us has time. We have to depend on the algorithms—and we're not asking key questions, like: what does that do to our autonomy?

If an AI is deciding, hey, De Kai, you're never going to know this, and you're never going to know that, and you're never going to know that—that is a massive psychological manipulation. And it's completely unconscious, because guess what? I'm never going to know what the AI didn't show me. We don't know what we don't know. We don't know what we're not shown. So we can't even point at it. It's so insidious.

It's not like fake news or deep fakes—you can point at them and say, hey, this is false, right? It's not like bad actors—you can point at it and say, hey, this piece of information got shared by somebody I've labeled a bad actor, which is basically a political notion that says somebody on the other side, right? Nobody's a bad actor in their own head; it's the other side that's the bad actor. And so we keep on obsessing on pointing those things out, but what we're ignoring is that the biggest manipulation of our unconscious is through the power of these algorithms to decide what they're never going to show us—what they're going to censor from our view.

That's how we lost our autonomy 10 to 20 years ago already. And we just—we don't know. We walk around telling ourselves comforting mythologies of our free will, our sovereignty, our autonomy, our self-determination. That's part of our human aspirations, our belief system. We unfortunately operate in denial of how much autonomy has already been taken from us by the power of those algorithms to decide what we will never see.

I think reclaiming that is really important. I think, to the second part of your question, AI is the best technology humanity has ever invented, that has the power to actually help us overcome that. AI is the one thing that could, at scale—for 8 billion people—actually show us: here's what you don't know. Here's perspectives you haven't thought of. Here's evidence that you've been ignoring. Here are things that you've been too biased to look at, and so forth.

AI is the one thing that could, at scale—for 8 billion people—actually show us: here's what you don't know. Here's perspectives you haven't thought of. Here's evidence that you've been ignoring. Here are things that you've been too biased to look at, and so forth.

AI absolutely could help us reclaim that, both individually and collectively as a society, and it's absolutely essential that we begin to deploy AI that way in order to stop this horrible slide we've been experiencing—where we've been deploying AIs the opposite way, causing us to understand each other less and less, and to operate in denial of facts in the real world because we don't want to look at them. The online AIs make it so easy for us to avoid looking at them.

It is the height of irony that, so far, the advent of the AI age has been dragging us back to the Dark Ages. It's pre-empirical thought, pre-Enlightenment and Renaissance thinking, pre-critical thinking. It is the height of irony when, in fact, AI has the potential to create a new age—an AI age—of Enlightenment. And I firmly hope that the messages that I and allies are trying to get out will help us to say: Hold on. We, as a people, need to be debating this in our living rooms.

We need to sort of come to an understanding that “law of the jungle” is not a good basis on which to build our information infrastructure in the age of AI and information. It is an essential resource, just like water and electricity and natural gas were in the 20th century—in the industrial age. We also need dependable, reasonably clean, and reasonably balanced sources of information, just like all the other infrastructures. Let's figure out how to do that, instead of just sweeping under the rug the questions of: Well, what are the criteria that our algorithmic sensors use when they decide what they're never, ever going to show us?

INL: If our online interactions are now training AI, how can we ensure we’re teaching it to honor the richness and diversity of human culture the same way we protect biodiversity in the natural world?

De Kai: That's a great question. I think there are two ways that we can do that—at least two ways, but two very important ways. First is by our example, because, as with any human children, the AI's are learning their behaviors, their judgments, decisions, and actions from us. And so, if we model honoring richness and diversity, then they will pick it up. If we constantly are reading or watching things from a very diverse set of rich inputs—from different angles, perspectives, cultures etc.—that's what our artificial children will learn. But if we always just stay in our own narrow perspective, then that's what they will learn.

So, at the end of the day, no matter what folks like me do in working with the policymakers and the regulators—no matter what we do, no matter what we get the big tech companies to do—we, in the end, are still the training data. We are the role models. And so, whatever big tech does—garbage in, garbage out. You've probably heard this saying about children: that it never works to do what I say, not what I do. Right? Never works.

Good kids will do what you do, and they'll ignore what you say. Artificial children are going to be the same. We have to understand the necessity of us now behaving as good role models. For people who have kids—if you ask them: what is the single event that made you most want to become a better version of yourself?

A huge majority of them will say, oh, having kids. Because the second you see that little toddler sitting there, like, smoking something, you're like, oh my God—I need to shape up. And that is exactly what our artificial children are. That's exactly what our AIs are—and they're even more powerful in reflecting that back into the world.

So we need to step up and show them how to honor richness and diversity of human culture, same as we protect biodiversity in the natural world.

Then the other way is: what about the schools where they're training? We send kids to school, but a huge number of parents think, well, where should we settle down? We want to be in a good school district because we care about what schools are going to. Then we're like, oh, we need to meet the teacher. So we have meetings with the teacher regularly. Then, for some, we're going to join the Parent Teacher Association so that we can have more input. And some people run for school boards. Then you have statewide networks of all the PTAs. Then you have nationwide PTAs for all 50 states.

Where is that for artificial children?

The schools are the big tech companies. The machine learning engineers that train the AIs are the teachers. Administrators in those companies are setting the curriculum, designing the curriculum.

How is it that we're falling down on the job here as parents—on something that we so naturally do when it's human children—but now, with these artificial children that are so much more impactful and influential in our society, we're not doing any of that?

So that's the other component of what I'm doing in the book. I'm actually enlisting everyone to help join networks of PTAs to deal with the tech companies that are the schools.

INL: The phrase ‘ethical AI’ has become easy to say, but hard to trust. What does meaningful ethical responsibility look like in a space shaped by power and data?

De Kai: This is really interesting, because there is a difference between ethical AI, and AI ethics, and ethical deployment of AI. What I mean by that is: an ethical AI, to me, is an AI that has its own ethics, its own morality—just like you would want an ethical child, or an ethical adult. You want an ethical AI—one that has a sense of what’s, if not right and wrong, what’s good to do and what’s not good to do; how to make judgments.

I think AI ethics encompasses that. It also encompasses how we deploy different kinds of AI in ethical ways. And so here, it's more onus being put on the human deployers of it. I think both are important.

The first one: we need to raise AIs that are ethical by themselves. And we need to get away from this old-fashioned 20th-century idea that AIs are like computer programs that are logical—that you just write rules for. Because modern AI is not that. Modern AI is just simulated large neural networks, just like our brains. And they're not logic-based, actually. It's just easier to build large-scale simulations of complex, dynamic systems—like our brains—in a computer rather than trying to build it in hardware.

It's just like how we use wind simulators when we're designing airplanes or automobiles. They're complex, analog, dynamic systems—and that's what modern AI is. So teaching them to be ethical is necessary. You can't hard-code the ethics into them. They're not logic machines.

Just like human children, we have to nurture that.

On the other hand, we certainly also need to have a lot of public discussion and guidelines on what are ethical ways for humans, companies, etc., to deploy systems with a lot of AI models in them. Governments around the world have been taking initial stabs at that. The European Union's AI Act8 is the most ambitious sort of vanguard. And the think tank that I serve on the board of—TFS9 (The Future Society), along with the Future of Life Institute10—actually drafted a bunch of that to try to see if we could improve things.

I think one of the issues there: it's very hard to write rules that will force the companies to be responsible. Rules, for one thing, are always in conflict with each other in any real-world situation. Anybody who's read Isaac Asimov's iRobot stories—he only had three and a half rules (think of them as three and a half laws)—and yet he wrote dozens and dozens of stories, each of which was basically predicated on how two of those rules were in conflict with each other in the real world. That's when you only have three rules.

If you try to write legislation that has a thousand rules in it, it's just going to be a total mess. Everything will be in conflict—because everything is a trade-off. In normal human society, we understand that. We understand that there's a lot of trade-offs.

What we need to do is to update that mental model to include AIs—as well as humans—in that picture, and not to assume that we can just write rules that are going to dictate responsibility. The rules will catch extreme abuses, but we need to see this more as a cultural problem, the same way that we look at ethics in human society.

INL: Your work is inherently multi-linguistic—spanning across cultures, to music, and even more-than-human world communication. How can multilingualism offer resilience—in a world under social and ecological strain?

De Kai: When we talk about multilingualism, what we're really talking about is having more than one language in which to frame ideas, to frame descriptions of things in our world—and that each different language gives us a different perspective.

You know, there are things that are just super easy to say in English, from which you can draw generalizations, and are almost impossible to say in another language—say, in Chinese—and vice versa, right? Something that is just super natural to say in Arabic becomes like, “Oh, I have to write a paragraph about this in English.”

It's not even just extreme examples like Arabic, English, Chinese. This even applies to American English—the way that, say, Californians talk versus the way that my family in Kansas City talks versus the way people in Florida or Maine talk. These all are kind of different languages—sub-languages—because, about the same issue, they will use completely different vocabulary. They will use vocabulary that frames a particular way of looking at the world, reinforces particular perspectives, and negates or disregards others.

In a world where it is so important for us to understand each other, and to understand where each other are coming from so that we can actually focus on problem-solving—instead of getting hung up on people not even understanding the challenges that other people are facing, or people just lobbying insults at each other—we really need to be in a place where we're able to think of it as something in California English, but also think of it in Kansas City English, and also think of it in Florida or Maine English.

That's kind of a dream, AI-wise, that I've been thinking about for quite a while—advancing from a kind of primitive language translation to cultural translation. I think that's absolutely critical. We need to get away from this notion that there is a single, universal, absolute truth to everything. I mean, sure, if you're doing hard mathematics or hard, hard science—sure, okay. But most of the things we talk about have to do with values, and social norms, and cultural norms, and things like that. There is no black and white: “This is true,” and “This is false.” There's many different ways of looking at it.

The faster we get to a situation where we can adopt a translation mindset—where we very rapidly look at the same thing from many different perspectives, couched in different language—the better chance humanity has of surviving and flourishing in the AI age.

The faster we get to a situation where we can adopt a translation mindset—where we very rapidly look at the same thing from many different perspectives, couched in different language—the better chance humanity has of surviving and flourishing in the AI age.

INL: What feels most urgent—and most possible—when you imagine a future shaped by empathy, shared language, and ethical artificial intelligence?

De Kai: Oh, this is a really good question. I think that AI has been causing a lot of social stresses, a lot of issues domestically in many countries, as well as geopolitically. And I also think that AI is the best tool ever invented that could compensate for that—if we would just develop the social will to deploy it that way.

In spite of market forces—because, let's face it, it's not profitable to avoid outraging people. Driving fear and hate and outrage is very profitable. It allows advertisers to get more engagement, because once people are triggered, they just keep on spending time on those sites. That's not terribly good for society. It's good for whatever company is running those AIs, but ultimately, we could instead—if we could find a way to overcome the market dynamics—we could instead be deploying AIs that are helping us with empathy.

Empathy is hard. And when I say that, I don't mean just affective empathy. It is emotional empathy. So that's kind of like, oh, you're crying, I start crying too. I don't really know why. It's like—some people have called this mirror neuron. It's kind of our unconscious mental processing that does that. We don't really know why.

But then the second level of empathy is cognitive empathy. And cognitive empathy is where you are actually thinking, reasoning about, oh, you know, why are you crying? And you realize, oh, because you have lost your job, and your children will have no ability to get their medical shots or afford the school tuition. And it jeopardizes their whole future. And if only somebody would give you... right? So that kind of reasoning is cognitive empathy, and it's demanding.

Yet you have to put yourself into the heart and soul of someone who has probably a very different lived experience from your own. You have to work extremely hard at imagining yourself in their shoes—when you've never been subjected to a lifetime of the traumas that they've been subjected to. Most of us are very busy and go day to day and don't have much time to do that for everyone—that kind of cognitive empathy. But again, AIs are the best thing we ever invented that could help us with that.

I'm fond of saying—it's like the way Google Maps, which is a very specialized and narrow kind of AI, helps me with my deficient spatial orientation. It sort of augments me in cognitive skills that I am challenged in.

We could have AIs help also with empathy—especially cognitive empathy. It could help us to understand: “Oh, De Kai, you're using Californian language to understand this situation. Here's how your Kansas City uncle is languaging it instead, and why he's drawing conclusions that you're not.” Let's see if you can be empathetic toward each other. How could we get past the surface and actually look at this: how could we come up with a win-win that solves both our concerns?

I believe AI can do that, and I'm hopeful that we can build that tech. But I need all of us—everyone—to help to generate the social will, against profit interests, to deploy that for the health of our democracy.

You can learn more about De Kai here, and pre-order his upcoming book Raising AI here.

The Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, also known as linguistic relativity, is the theory that the language we speak shapes the way we think and perceive reality. Named after linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf, the hypothesis suggests that linguistic structures influence cognitive processes, meaning that speakers of different languages may experience the world differently based on their language’s vocabulary, grammar, and syntax.

Deontological Ethics is an approach that emphasizes duties, rules, and principles over consequences. In this view, certain actions—like telling the truth or keeping a promise—are considered morally right regardless of their outcomes. This framework is often associated with philosopher Immanuel Kant, who argued that morality is grounded in rational duties and universal principles.

Consequentialist Ethics is an approach that judges actions based on their outcomes. What matters most is the result—if an action leads to the greatest overall good, it is considered morally right. This framework is often linked to utilitarianism, notably developed by philosophers like Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, who emphasized maximizing happiness and minimizing harm.

Virtue Ethics is an ethical framework that focuses on the character and virtues of the individual rather than on rules or consequences. Rooted in the philosophy of Aristotle, it emphasizes traits like courage, honesty, compassion, and wisdom, suggesting that ethical behavior arises from cultivating a good character over time. Instead of asking "What should I do?" virtue ethics asks "Who should I be?"—highlighting moral development as a lifelong practice.

LLMs (Large Language Models) are advanced AI systems trained on vast amounts of text data to understand, generate, and predict human language. They use machine learning techniques, especially deep neural networks, to analyze patterns in language and produce coherent, context-aware responses. Examples include OpenAI’s GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) and Google’s Gemini.

Law of the jungle is a phrase popularized by Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book (1894), originally describing the survival rules observed by animals in the wild. In this context, it implies a brutal natural order driven by competition and survival of the fittest. The speaker uses it here as a framework to emphasize the raw, unforgiving evolutionary pressures that shaped humanity over millions of years. However, it’s important to note that this interpretation is debated: many natural ecosystems and Indigenous perspectives emphasize cooperation, balance, and mutual respect alongside competition. While “law of the jungle” often symbolizes harshness and survival struggle, it can oversimplify the complex social and ecological dynamics in nature. The usage here underscores the urgency of moving beyond such primal competition, especially given the unprecedented challenges posed by AI and modern weaponry.

Systems thinking is an approach to understanding complex phenomena by viewing them as interconnected wholes rather than isolated parts. It emphasizes the relationships, patterns, and feedback loops within systems, helping to reveal how changes in one area can impact the entire system.

The European Union’s AI Act is a landmark regulatory framework proposed by the EU to govern the development and use of artificial intelligence, aiming to ensure safety, transparency, and ethical compliance based on risk levels.

The Future Society is a nonprofit think tank focused on addressing governance challenges of emerging technologies, particularly artificial intelligence, through policy research and international collaboration.

The Future of Life Institute is a nonprofit organization focused on steering transformative technologies, particularly artificial intelligence, toward beneficial outcomes for humanity.