The Bigger Picture Uniting Us All with Helena Norberg-Hodge

Local economies as the key to health, happiness, and real prosperity.

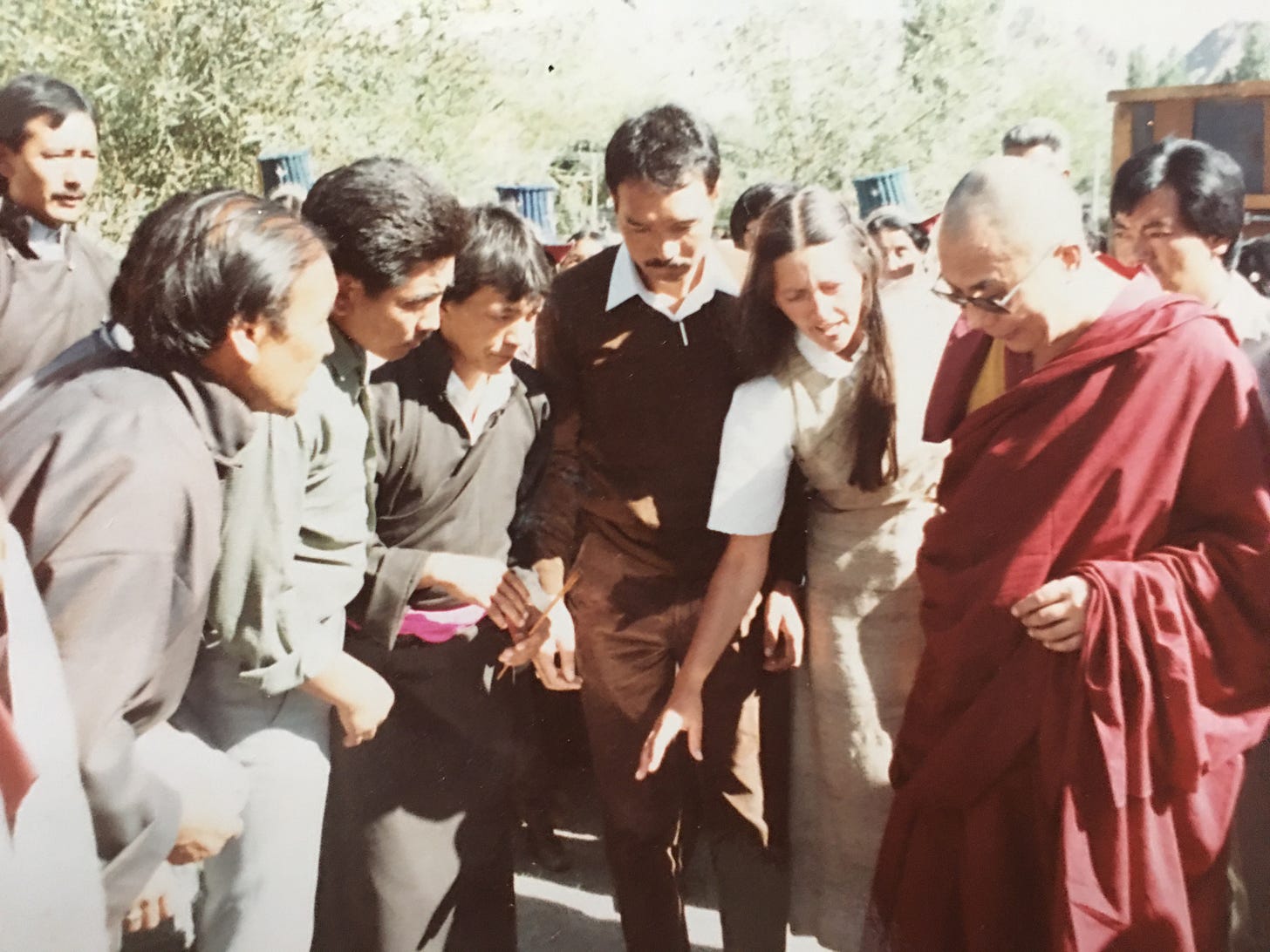

Linguist, author and filmmaker, Helena Norberg-Hodge is the founder and director of the international non-profit organization, Local Futures, and a pioneer of the new economy movement. She has helped to initiate localization movements on every continent, and co-founded both the International Forum on Globalization and the Global Ecovillage Network.

Her dedication to raising awareness for localization stems from her experiences and observations of the negative impacts of globalization, particularly on traditional cultures and ecological systems.

This interview has been transcribed from audio.

INL: Globalization, the interconnectedness of economies around the world, has been touted as a force for progress. However, globalization has contributed to growing social and economic inequality, environmental degradation, and the erosion of cultural diversity.

Do you think shifting back to localization is the panacea to these problems?

Helena: Without a doubt we need to shift towards localization. In order for people to understand this, they need to have a closer look at what globalization really is.

It has been a process whereby national governments around the world sign trade treaties to give global corporations and banks, more and more power. Clauses in the trade agreements, called ISDs (Investor State Dispute settlements) are unbelievable. They demand that governments sign in black and white: ‘We will not do anything that might reduce your profit. If we do something that may cause you to earn less money, you can take us to court and sue us’. So that's what's going on. There are thousands of cases of big businesses suing governments because they’re trying to protect the environment or their people and it threatens to reduce the profits of these corporations.

I would argue that if people were aware of what's happening because of globalization, the majority would insist that governments shift policies away from the support of big global monopolies that generally do not pay tax, and have relaxed or no regulations.

You and I are paying taxes. We're squeezed by regulations. Meanwhile, global corporations are using genetic engineering or nuclear power — tools that have the potential to contribute to ecocide around the planet, or even affect life on Earth forever.

Supporting global free trade means supporting no rules for global corporations, no rules for Walmart, for Monsanto, for Pfizer, for Cargill. Understanding the reality of this economy, it’s clear that we need to support the adoption of localization.

INL: You’ve said that raising awareness for how the global economy operates is essential for our transition away from it. What are the fundamentals that we should all know?

Helena: Well, I would say that the most important thing to understand is what these trade treaties actually mean and how long they’ve been going on.

It all started after World War 2, when the Bretton Woods Institutions were set up, which were the World Bank, the IMF and something called the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade).1

It became commonplace for governments to open their doors to global corporations despite people on the left critiquing capitalism and the way the IMF and World Bank were imposing loans, particularly on the so-called Third World. This was the beginning of the handover of power to global corporations.

The broader systemic effect of supporting global trade has not been very well understood, and there's been very little opportunity to talk about it, either in academia or the media. We have to look actively for honest information and holistic descriptions of what's going on, because otherwise we can fall into a story of rich countries versus poor countries. It's an analysis that makes every Westerner feel guilty about exploiting the rest of the world.

The last 500 years saw the rise of the modern global trade-based economy. The system set up by European traders was based on enclosures in the West, and slavery in what became the “3rd world”. Their values were explicitly patriarchal, misogynist and anti-nature. In Europe, people were driven off the land through enclosures so they could become cheap labor in factories, manufacturing the cotton from India or the tea from somewhere else.

Later on, in the “3rd world”, where colonies were supposedly liberated, they were enslaved economically. The economic forces continued to push farmers away from cultivating a diversity of products and towards the production of one product, specifically for export.

Global trade that encourages monoculture on the land is the enemy of healthy economies and ecosystems.

We also need to look at the social impact of the global economy. In Ladakh, or Little Tibet, and Bhutan, I witnessed traditional cultures, untouched by colonialism. Even in rural villages in Spain, as late as the 80s, I had the privilege of experiencing communities where the extended families and close relationships to the land were still alive.

It's important that we go back and understand that before the advent of this global, dominant economy, people all around the world depended on a larger group to meet their basic needs — food, childcare, healthcare, etc. They needed each other. So we were never self-reliant, throughout our evolution we were community-reliant.

We had an extended family, community fabric and much smaller economic units where we knew each other and depended on each other. And in that larger fabric, particularly the extended family was important for a healthy identity for children, and also important for the elders because they had the vitally important role of looking after the young children. They were mentors for their whole lives. I lived that experience in Ladakh and Bhutan and to some extent in Spain, and saw how that contributed to a strong sense of self, to deep self respect and happiness basically, a joy that comes from being alive and feeling that you have purpose.

INL: Across Europe and India, farmers are holding large-scale protests, fueled by rising costs and unfair competition from cheaper imports — a direct consequence of globalization. Some are calling for policies that support local food systems and reduce reliance on long-distance food transportation.

What are the biggest challenges in transitioning towards localization within food systems?

Helena: The biggest challenge we face is that global monopolies are funding virtually every avenue of knowledge: they are funding whole departments in academia, as well as mainstream and social media. They are preventing the information that needs to get out about the way that our taxes are subsidizing global trade — are supporting global trade.

This whole system has been driving farmers to produce only one thing. And that thing has to be a standard size that fits the machinery that harvests, washes and then puts it on the supermarket shelves. All of this is completely unnatural, and these products appear in the market place as though they are cheaper. They are only cheaper because of the way that our governments are using subsidies, taxes, regulations and laws to further the project of supporting extractive wealth for global corporations.

Therefore to shift, is not an easy thing.

Many are becoming aware of the poor quality of food at supermarkets and are now understanding that healthy food is the most important medicine. We understand that chemical, industrial and corporate agriculture isn’t only the biggest threat to ecosystem health, it is the biggest threat to nature overall. Many are engaged in projects to link with farmers near cities, or create farmers markets to gain access to healthier natural food that has been transported much shorter distances. These initiatives are growing all around the world. It's common sense. It brings with it wonderful side effects because it helps build community.

One of the most beautiful aspects of community building for me, has been seeing farmers who are quite conservative and not very ecological, those that had been pushed to use more and more chemicals, now in the farmers markets. Generally, the consumers are quite concerned about having fewer chemicals and wanting more natural food. This becomes the most beautiful symbiosis where these political leanings fall away and you're creating mutually supportive structures.

As one farmer said to me, “I grew up as a farmer, I've been a farmer my whole life. We were pressured to produce standard size and larger and larger quantities for less and less money. Now, after starting at the farmers market, it's like being in a different galaxy. Now, every avocado, whether big or small, is bought. Now, every avocado, whether it has a few blemishes on it or not, is sold.”

The farmer is now getting 80-100% of what we pay. In the dominant system that is subsidized by our governments, the farmers will only get as little as 5% of what we pay. Awareness is growing that supermarkets have become these huge thugs, treating farmers badly and deceiving consumers. Localization is the biggest threat to this system. When we come together at the local level, we start transforming the whole economy2. Instead of being dependent on huge monopolies, we become dependent on one another. And we create human-scale institutions that are more accountable and visible.

INL: You’ve said urbanization is a major contributor to the polycrises we’re facing, eroding local self-reliance, cultural identity, and environmental sustainability.

Can you explain this further?

Helena: The link between globalization and urbanization has been there from the outset. People being pushed off the land into cities has allowed the concentration of wealth to reside in the hands of global traders.

Today, one of the most urgent issues is to raise awareness: that when you shift people away from decentralized livelihoods, e.g., away from smaller towns and cities where the food they consume, the water they use, the wood and the building materials needed are all nearby, into today's big megacities, every resource from water to energy to food has to come from far away. As people are driven off the land, they are replaced by large scale, energy and resource intensive technologies. The growth of megacities is an absolute disaster.

Understanding the link between this urbanizing path and global trade is crucial. This includes, importantly, the trade in money. Investors are able to extract more wealth as people are shifted to larger and larger megalopolis and sprawling suburbanized conglomerations. The concentration of people in these man-made areas everywhere is driving up energy and resource consumption of every kind.

Urbanization is linked to the imposition of monoculture on the land and the inability for humanity to creatively engage with the healing of nature by respecting and nurturing diversity—which is absolutely essential. After almost 500 years of abuse, we need to enable people to wisely and creatively nurture back to life the diversity on which we all depend.

We can see that, everywhere around the world where wilderness is being restored or protected, it’s people on the ground. We can see what happens when we support localized, diversified agriculture—the work becomes enjoyable, and it involves more people on the land. More hands, more eyes, more hearts and souls that care and can respond to that infinite diversity of the living world.

INL: “We evolved in community groups, we evolved close to nature. And that’s who we are. That’s what it is to be human.” Can you explain what this means to you?

Helena: I am sharing what I’ve learned from the wisdom accumulated over hundreds and thousands of years on the Tibetan Plateau in Ladakh, where I lived and worked for more than 40 years. It was an amazing privilege getting to know people who lived in extended families with a strong community fabric, where every mother had five caretakers, or more, for every child, where the deep bond between the oldest and the youngest was one of the most beautiful things I've ever experienced. It was a bond which was reinforced by the daily care involved in practical work.

It was economic in the sense that it provided huge support for mothers who hadn't put their children in an institution in order to go to work. The child was with their grandmother or with a great uncle. This extended fabric of human interdependence was so clearly how we were meant to live and one of the main reasons why people were the happiest, most vital, and healthy I had ever experienced.

That's how we evolved in nature. Closely connected to one another, as well as to the animals, to the plants, to the water, to the soil, to the trees that provided for us. We knew that we were a family and of course, we knew that we had to give back.

I had the great privilege of living in this localized indigenous culture, and of knowing how much happier, stronger and healthier I felt when I was living in these communities, as opposed to how I felt when I went back to the West, where I was trying to share this information. Living an industrial, speedy, competitive lifestyle — I could feel what it did to my health, both psychologically and physically. I could feel the difference between living in a country where there were no mirrors, and coming back to a world that seemed to be only mirrors.

As the camera and social media started taking off, it was so clearly a step in the wrong direction and one of the reasons why, now, the suicide rate among young girls is one of the most rapidly growing. We really need to wake up to the bigger picture. And the wonderful thing is that when we do wake up, so much of the self-blame and self-rejection falls away. We understand that we are victims of progress and we can turn to each other in our openness and vulnerability, and feel love and compassion for others, as well as for ourselves.

There is a path forward that is rebuilding the fabric of the community with the rest of life. When those two things happen together, they create an amazing healing path that brings joy and health almost immediately, I cannot overstate that.

INL: You founded the international nonprofit Local Futures, dedicated to the worldwide localization movement.

What is the ultimate vision? What do you think is possible?

Helena: ‘Local futures’ is consciously plural. Just like my book, Ancient Futures3. I'm essentially talking about futures that will be cultural expressions of diversity. I am convinced that this will happen. It's a future where we wake up to the fact that we are part of nature. We wake up to the fact that we have, in an unconscious way, supported a path that's actually deadly. Conventional schooling, conventional media and virtually every avenue of knowledge has taken us down a path of progress that has been anti-life and systematically removed us from lives we didn’t even know we were losing as we were herded into cities.

As people have gone into that life of the urban consumer culture, they have developed a yearning for nature and reconnection. We’re seeing that with people who've done well out of the conventional economy, and can afford to do so, they choose to come back to live closer to nature and very often in places where there is more community.

This local future is being built right now and it's taking us back home to the fundamentals of what it is to be human. It reminds us to respond to the complexity and diversity of life.

What happens when we live in a relational way with humans and more than human life?

We are aware of our limits.

We must wake up to the need to localize economic activity. We've got to bring those reciprocal relations back to human scale, where we can see them properly. Not everything has to happen within a few miles radius. We’ve always had ways of life where trade went on even globally. But the main fabric of your daily life, how your needs are met and the people you depend on, this has the potential to be in deep communion with life.

There are local futures being born on a smaller scale around the world and we will see a rise in this movement as the crises’ caused by the dominant path increases — specifically with AI speeding up anonymity and narrow reductionism. I just hope to see it before I die. I'd like to see the awakening to the fact that our governments are locked into this secret support of creating a global empire that makes a few billionaires richer, while the majority of us are getting poorer.

We've got to be on guard against anything that is politics of identity. Let's not focus on the differences between different genders, different races, rich and poor. Let's instead look at the bigger picture that can unite us. The universal need for reconnection to nature and to one another. That is a truly universal human need.

INL: What can we all do to help with the transition?

Helena: For anyone interested in these ideas, visit the Local Futures website. We have materials for the path forward — the journey of conscious reconnection. We have tools to share with others. This is what we call ‘big picture activism’.

We want you to actively rethink fundamental assumptions about what you've been taught about progress, about happiness, about health. To look at this bigger picture and then to share it as actively as you can. Remember again that the dominant media channels are not letting this information out.

At Local Futures, we have voices from every continent sharing this bigger picture. Hopefully this global united voice can strengthen the movement back home to nature, back home to community, and back home to ourselves, to the Self inside us. Our souls long for that reconnection.

INL: What does Natural Law mean to you?

Helena: Natural law to me means that nature gave birth to us. Nature shapes us and we need to abide by the very clear instructions she's been giving us.

It comes back to diversity and to interconnectedness. It comes back to constant change and growth in cycles as we continue to evolve.

The GATT was superseded by the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. While the GATT as an independent organization is no longer active, the trade rules it established continue to be a foundation for international trade regulations.

By shortening the distance between consumers and producers, we structurally encourage diversity on the farm – which in turn means greater productivity, more local livelihoods, more nutritious food and healthier ecosystems. Watch Local Food Can Save The World.

Ancient Futures challenges us to redefine what a healthy society means and to find ways to carry centuries-old wisdom into our future.